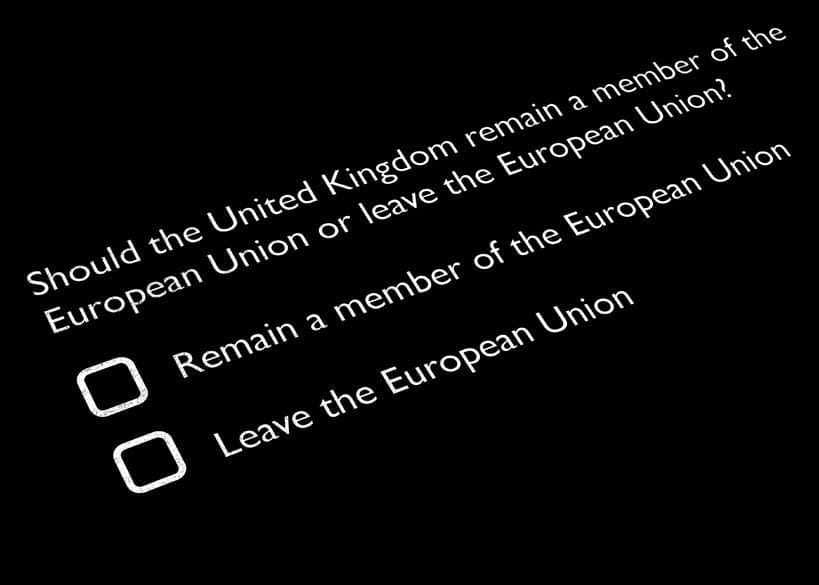

Some View EU Olive Oil Decree as 'Last Straw' in Brexit Vote

When British citizens cast their historic vote tomorrow to stay in Europe or leave the Union, many will be thinking about overreaching mandates like the ban on cruets in restaurants.

As part of a host of sweeping regulations put forth by the EU’s Commissioner for Agriculture in 2013, serving olive oil in open, refillable cruets and containers on restaurant tables was to be banned. The measure was representative of a series of new and overarching protocols and procedures designed to be adopted by the entirety of the European Union.

Not all countries were on board and some have been bristling against being told by EU’s governing body how to run their businesses in what they still consider to be sovereign territory. The push-back on this topic represented a microcosm of some of the issues that underlie Great Britain’s upcoming “Brexit” vote. Tomorrow, the United Kingdom will vote on whether or not to exit the 28-nation Union altogether.

Was the olive oil decree the last straw?

In May, 2013, Julie Butler reported in Olive Oil Times that countries who favored the new rules for serving olive oil included, not surprisingly, the territories where much of the world’s highest quality olive oils are produced — Italy, Spain, France and Greece, among them. Voting against the move were nine countries, while the UK abstained.

But in a post on ABC News, the AP’s Raf Casert pointed directly to the olive oil controversy as an example of the underlying resentment that may be fueling the “British Euroskeptics who have railed for years against what they see as the EU’s excessive intrusion into daily life with a long list of petty rules.” Here was a case in point of “overreach that promised to irritate everyone who loves to dip crusty bread into oil,” he said.

The rule required food-serving businesses throughout the EU to use only carefully packaged and labeled olive oils in non-reusable containers, their origin and make-up clearly marked. The goal of the measure was to set standards for a category fraught with counterfeits and controversy. They were designed, as noted in Butler’s article, to “better protect and inform consumers while ensuring the quality and authenticity of olive oils,” and to stop the practice of serving patrons products which are adulterated and cut with cheaper oils.

The plan, however, found little support among British citizens, prompting scores of complaints, and in the end, was never actually put in place. Casert spoke with Steven Blockmans, an analyst with the Center for European Policy Studies, who noted: “The plan to ban open olive oil dispensers came after many in Britain were already used to mocking perceived EU diktats. It may well be the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back,” Blockman said.

Whether as a result of the olive oil controversy itself, or the real possibility of the country exiting the EU, the EU governing body in Brussels appears to be listening to the Brits, promising to focus on broader matters, being “big on big things and small on small things,” and cutting red tape for participating countries. Though this may appease the British voting public to some degree, the translation for them as consumers means it’s likely they’ll continue to be dipping their bread in what they think is EVOO, when in fact they’re sopping up a hybrid of cheaper, less healthful oils.