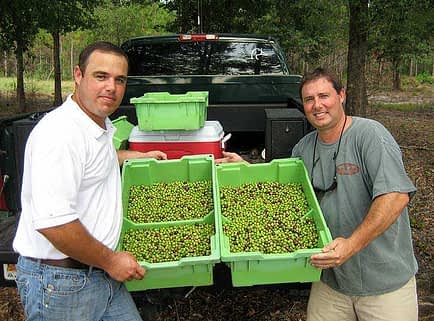

Sam Shaw (left) harvesting olives at Georgia Olive Farms

How Georgia’s olive oil industry got its start is an interesting tale of parallel paths towards the same goal. On one path, Georgia State Legislator Mary Squires was looking for ways to improve the Peach State’s agricultural base and set about researching the viability of growing olives. On another path, a few Georgia farmers were looking for a new crop to supplement their blueberry business and had a notion to plant olive trees.

There may have been cross-pollination of the two paths or it may have been just the perfect convergence of economic and climate conditions that resulted in the beginning of Georgia’s new olive oil industry.

In 2000, Georgia was experiencing a severe drought. The Senate Natural Resources and the Environment Committee was studying aquifer water sources and went on a field trip to southwest Georgia farmlands. Committee member Mary Squires met growers who attributed low crop yields not only to the drought but also to climate change.

When one farmer remarked that they needed to find a crop resistant to climate change, Squires’ research gene was activated. As a former warfare specialist in the Georgia Army National Guard, she had conducted many groundwater, air, temperature and soil studies. She “dusted off” her old research, plotted Georgia’s climate, soil and water data and started looking for crops that grow under those conditions.

Mary Squires

She realized that Georgia’s climate resembled a Mediterranean environment and she added olives to her list of possible crops. On a visit to the Savannah Trustees’ Garden, the country’s first public experimental farm operated from 1733 to 1748, she noticed a plaque confirming that olives were once grown at the site.

Squires connected with a peach horticulturalist from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and shared her olive discovery. The researcher indicated that there had been no varietal trials of olives conducted in the region since Thomas Jefferson’s efforts.

In 1791, Jefferson acquired olive tree seedlings from Europe and sent them to South Carolina for planting. He said that among plants, olives “contribute the most to the happiness of mankind.” Unfortunately, the trees did not thrive and the experiment ended.

The USDA researcher studied historical records and concluded that the olive tree failure was due to cold temperatures and to using the wrong cultivars. Further, she obtained data indicating that there were 14 varietals that could potentially grow in Georgia and she proposed planting one of each varietal as a test.

Squires asked for a cost estimate and a formal research proposal that she could use to acquire private funding for the project. In 2007, the project was funded and the trees were planted in a greenhouse.

In 2008, the economy collapsed, jobs were lost and the researcher found a position elsewhere. The trees were left untended and died. Squires was devastated by the loss and says her involvement in olive research “died in the ground in 2008.”

Her efforts instead turned to promoting the Georgia and U.S. olive industry wherever she went and she “became a poster girl for olives.”

Meanwhile Shawn Davis, a Georgia blueberry farmer, had consulted with the same USDA horticulturist as Squires. Davis was predicting blueberry crop surpluses and wanted to branch into new crops. In 2007, he decided on olives and planted 14 acres, reported Jennifer Paire and Curt Harler (Growing Magazine, Feb 2011). Davis became one of the founders of the George Olive Growers Association.

Jason Shaw

About the same time, the Shaw family decided to experiment with growing olives. Jason Shaw, now a Georgia State Representative, says that he and his brother Sam were “always interested in innovation” on their farm. They consulted with John Post, an agricultural advisor from California, and with the University of Georgia Cooperative Extension to determine if olives could grow in their part of the State, near Lakeland.

They were encouraged to give it a try and installed super high density trees that could be picked by the same machines they used for harvesting their blueberry crop. “We had the coldest winter on record,” says Shaw, but the trees “came through OK. ” They considered it a good test.

In 2009, Jason, Sam, their cousin Kevin and friend Berrien Sutton formed the cooperative Georgia Olive Farms. Their first harvest, and the state’s first commercial harvest in several centuries, took place in late 2011.

Olive consultant Nancy Ash conducted a taste test and called the extra virgin olive oil “sweet, smooth and soft,” and Australian expert Paul Miller also gave the oil a positive review, reported Jim Auchmutey in last Atlanta magazine.

Shaw says that they have received great press and much support for their efforts from many corners, with the food industry and chefs being particularly supportive.

Georgia Olive Farms is adding acreage and is not yet at full production, Shaw indicated. He added that they bought a small mill and did their first olive oil milling this year.

The cooperative owners want to help build the Georgia olive industry and are offering their assistance to other farmers. They will arrange for the purchase of Arbequina, Koroneiki and Arbosana trees and help with initial olive farm management, but they warn farmers that getting into the industry is still risky.

Sam and Jason Shaw

Shaw notes that there are a few farmers adding olives to their orchards, but most are waiting to see if Georgia Olive Farms has another good crop year. “All eyes are on us,” explains Shaw. He believes that if the crop is good, there will be a big jump in farmer interest.

Co-owner Berrien Sutton thinks the lack of mills has limited plantings by other farmers, but Georgia Olive Farms will be establishing a processing center that will help other growers get started. He expects that by 2015, there will be six more orchards in Georgia in full production. By 2018, he expects 2,000 acres to be planted with “exponential growth” after that.

If Sutton’s predictions prove right, Georgia is on the brink of a major new industry. Although Mary Squires’ experimental olive trees died years ago, her dream was realized by the Georgia farmers who had their own innovative and intrepid dreams. As a result, today there is olive oil in Georgia.