BERKELEY, Calif. — Call it the EVOO evolution. Extra-virgin olive oil, once the domain of Spain and Italy, is popping up in surprising new places.

It’s on the up-and-up Down Under, growing in Croatia and is becoming such an industry in South America that a Chilean producer is bringing two products to the U.S. market this year.

The boom is fueled by two developments, a growing appreciation of extra-virgin olive oil as a healthier fat and technological advances that have made it more cost-effective to harvest, says Curtis Cord, executive editor of the Olive Oil Times.

“Just about anywhere it’s possible to make olive oil, it’s become a desirable crop,” he says.

Anywhere is right — there even are fledgling olive oil industries in China and India.

Globally, Spain continues to be the powerhouse of olive oil production, with Italy second, says Cord. And Mediterranean imports continue to dominate available selections in U.S. stores.

But that may change. Chilean producer Olisur is making a serious run at the U.S. market. The company is exporting two lines, O‑Live & Co., extra-virgin olive oil for everyday cooking, and Santiago Limited Edition and Santiago Premium, super-premium products intended for sauces, finishing dishes, etc. The oils are expected to be available in all major markets by the end of July.

Olisur farms a 6,500-acre estate about 80 miles south of Santiago using the new, high-density methods that have been revolutionizing olive oil production.

In the past, trees were grown in beautifully spaced groves wide enough that harvesters could go in with nets and shake or pull the olives off. In high-density growing, trees are planted much closer and kept shorter. Olives are picked by a mechanical harvester that rakes the fruit off the trees, a quicker method that requires less labor.

There still are people who swear by the traditional, hand-harvesting method from older trees, notes Cord. But the advantage to high-density harvesting is that you can get the olives to the mill faster — within two hours at Olisur — while the olives are at their freshest. Olisur oil has an acidity level of .2 percent, well below the standard of .8 required for extra-virgin classification.

Until recently, the United States didn’t regulate olive oil claims, but that has changed with the U.S. Department of Agriculture adopting new standards. Extra-virgin olive oil must be cold-pressed, free of defects and with an acidity of no more than .8 grams per 100 grams.

Cost efficiencies mean that Olisur can be high quality without being high price, says Olisur president Jay Rosengarten. Prices for O‑Live & Co. range from $6.99 to $7.99 for a 500-milliliter bottle.

“They’re really estate-grown products. We own the trees. We harvest the fruit. We press the fruit. We store the oil. We bottle the oil. Essentially, you’re getting a fully integrated system,” says Rosengarten. “As a result, the quality is significantly better than the mass-produced commercial oils we’re seeing from other places.”

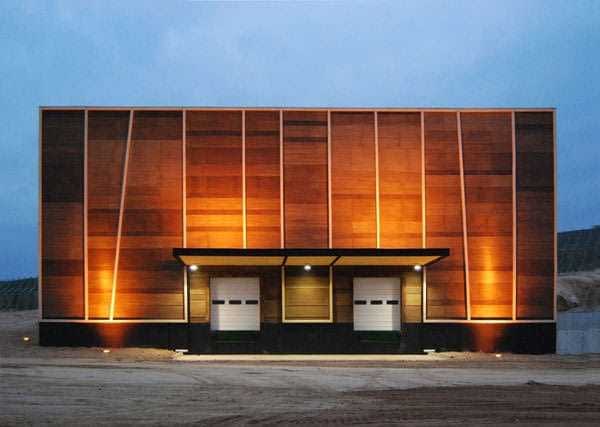

Though the olives are pressed only once, Olisur isn’t wasting anything. Leftover fruit is composted and used as organic fertilizer and the pits are used to fuel the generator that creates electricity for the factory, which is biothermally cooled by rods sunk into the subsoil that circulate ambient air.

In Australia, the olive oil industry began about 100 years ago for a very practical reason, says Paul Miller, president of the Australian Olive Association. It takes a long time to get olive oil from the Mediterranean to Australia — even longer back then — and this isn’t a product that benefits from aging.

Production has grown in recent years, with about 35 percent of extra-virgin oil produced going to exports, mainly to China, Italy and the United States.

A major producer is Cobram Estates, which is available online and in some specialty stores in the United States.

Australian olive oil is known for its fresh and fruity taste. The 2010 harvest is predicted to be about 4.8 million gallons. With technological advances, Australia could double production from existing trees and grow to producing about 1 percent of the world’s olive oil, says Miller.

California, meanwhile, went from about 6,000 acres of oil-producing olives in 2004 to 22,000 acres in 2009, says Dan Flynn, director of the Olive Center at the University of California, Davis.

So much for facts and figures, what about taste?

Susan Spungen, a former food editor at Martha Stewart Living magazine and food stylist who worked on the movie “Julie and Julia,” got a firsthand look at the Olisur farming methods as one of a group of food professionals invited to observe the recent harvest.

She was impressed by the speed with which olives were turned into oil, and the taste.

“We did a blind tasting and we had no idea what we were tasting. I and everyone else in the room said that our favorite oil was the one from the company that was giving us the tasting. You can’t really rig that.”

Santiago Premium won gold at Italy’s L’Orciolo d’Oro competition for the last two years, but Rosengarten says the company’s marketing approach is focusing more on Olisur as a producer of New World extra-virgin olive oil than trying to ape Italian products.

“The difference in our olive oil is it’s fresh,” he says. “We control the process; we’re constantly delivering fresh olive oil to the market.”