Award-Winning Importer Recounts Evolving US Olive Oil Culture

Tim Balshi co-founded MillPress Imports in 2000 after being inspired by the high-quality olive oil he tasted in Spain at the end of the 1990s. Over the past two decades, the company has carefully monitored and sourced extra virgin olive oil from various countries, working closely with farmers to ensure the highest quality. Despite the competitive nature of the market, Balshi remains optimistic about the future of olive oil consumption in the U.S., emphasizing the increasing appreciation for the product as a valuable addition to food.

MillPress Imports co-founder Tim Balshi has spent the last two decades importing high-quality extra virgin olive oil to the United States.

His passion for olive oil was kindled when he traveled to Spain at the end of the 1990s. “That was the first time I tasted fresh olive oil,” he told Olive Oil Times. “And I thought, ‘whoa, this is amazing.’”

This is a tough business. It’s a crowded market and getting more crowded by the minute.

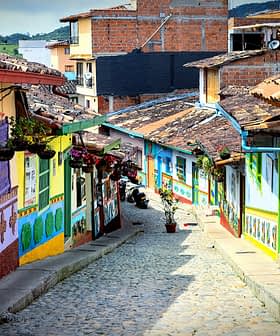

Even as Balshi completed his university degree and started working in the corporate world, his mind wandered back to the fresh olive oil he tasted in Jaén, the world’s largest olive oil-producing region.

Balshi felt he needed to share that same sensation of discovery with consumers in the United States. In 2000, he co-founded Aguibal with his cousin.

See Also:Producer Profiles“That’s when we started dabbling in importing” Spanish extra virgin olive oil to the U.S., he said. “We imported early crush oils back then before the internet really took off.”

Balshi and his cousin started by purchasing small lots of olive oil from producers Balshi knew personally in Jaén to ensure the quality was as high as possible.

At the time, Balshi’s cousin lived in California while he lived on the East Coast. “He’d cover the West Coast, and little by little, we would olive oil to discerning retailers and directly online.”

In the early 2000s, olive oil consumption in the U.S. was about half what it is now. According to the International Olive Council (IOC), the U.S. consumed 194,500 tons of olive oil in the 2000/01 crop year. In the past half-decade, consumption has hovered between 380,000 and 400,000 tons.

Back then, Balshi said olive oil was viewed as a commodity – a product where all units are indistinguishable and inherently have the same value. “It was a different era,” he said.

He attributed this to the lack of general knowledge about olive oil, especially among consumers in the U.S., and the absence of available information online and in the media.

“There wasn’t a real aptitude around high-quality oils outside of what we were doing and some other companies,” Balshi said. As a result, he sold most of his extra virgin olive oil to high-end retailers in coastal cities.

However, this all started to change in the mid-2000s when, Balshi said, producers in Spain and Italy were beginning to harvest early and produce high-quality olive oil at the expense of quantity.

“Producers were figuring out how to set up the mill at the right speed and how to bring in the fruit at cool enough temperatures,” Balshi said. “They were understanding the loss of yield and rolling it up into the price.”

Balshi said the culture around olive oil rapidly evolved in the U.S. after 2010 with media coverage of food and cooking, high-speed internet and awareness about olive oil’s health benefits.

“The advent of the internet really created more of a pervasive reach for olive oil producers and sellers and spread the values of olive oil and cooking,” he said.

Along with the more accessible access to information afforded by high-speed internet, Balshi said international quality competitions also played a significant role, with the introduction of the NYIOOC World Olive Oil Competition in New York in 2013.

However, as demand for olive oil has increased and the culture has taken root, Balshi said the imported olive oil market in the U.S. – which meets about 97 percent of the country’s olive oil consumption – has become much more competitive.

“This is a tough business,” he said. “It’s a crowded market and getting more crowded by the minute. Back then, it was mostly a couple of huge brands and all these little guys; we were one of them.”

As a result, the quest for the highest quality has become paramount. To that end, California has introduced its own definition of extra virgin olive oil with more strict physiochemical parameters than those outlined in the United Nations’ Codex Alimentarius, the IOC, and the United States Department of Agriculture.

To meet the growing demand for quality, MillPress Imports carefully monitors the sources of its extra virgin olive oil from Spain, Italy, Chile, Peru and South Africa, working closely with farmers and conducting extensive testing of fruit and oil every step of the way.

“We have people on the ground all over,” Balshi said. “We’re working with specific growers and mills to make oil to our specification.”

MillPress employees go to the groves before the harvest to test olives and ensure they do not have any pesticide residue or other pollutants. They are also there during the harvest, ensuring the olives are green while keeping an eye on the climate.

“There’s a two to three-week window to make green oil,” he said. “If it rains, you miss a week. If the fruit matures from green to a little bit riper, you may have lost some aroma or some quality. A lot of that’s up to Mother Nature, and that’s the hard part.”

After the harvest, company employees are also in the contracted mills, closely following the transformation process. The physiochemical parameters of the oil are then tested from the mill, and once they have arrived in the U.S.

“We have infrastructure that is set up for success and the quality mindset,” Balshi said. “We’re not a start-up anymore. We’ve been doing this for 20 years.”

Along with MillPress, Balshi is also involved with Almazara Aguilar, the mill operated by the family of his wife, Soraya Aguilar.

Aguilar and her family owned hundreds of hectares of rainfed traditional olive groves in Jaén and constructed a dedicated mill in 2007.

“Fast forward to where we are in 2023, and we’re looking to expand our groves in Spain and possibly in Portugal,” Balshi said.

Despite the drought, which Balshi and others have told Olive Oil Times will result in another poor harvest in Spain in the 2023/24 crop year, he is bullish about the future.

“I’m optimistic for the future of olive oil consumption in the U.S.,” he said. “Olive oil is viewed as a medicine and as a spice or condiment, something that adds value to the food now, and not just as a cooking oil with zero positive attributes like in the old days.”

“Now there’s more of an appreciation, so I feel like that’s not going away,” Balshi concluded.