Scientists Map Risk of Exposure to Xylella

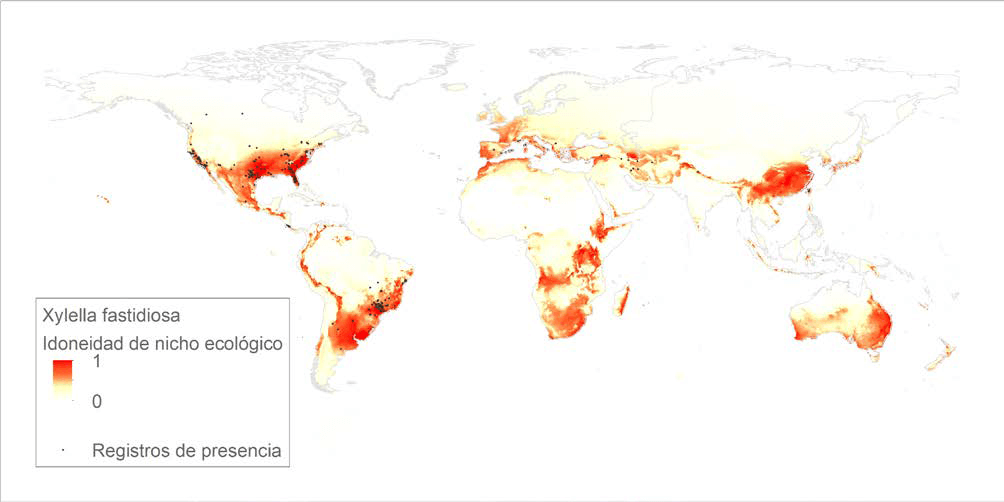

The study showed that southern Spain and other temperate locations between 40 and 50 degrees latitude are at the greatest risk for the spread of Xylella fastidiosa.

A leaf infected with Xylella fastidiosa.

A leaf infected with Xylella fastidiosa.A new study from the University of Málaga has revealed a broad bioclimatic potential for the expansion of Xylella fastidiosa.

The study, which was done by the university’s geography department, warned that increased areas of Spain and other countries with temperate climates are likely to be most exposed to this risk for expansion.

The success in the management of (biological risks) depends on our ability to predict the potential geographic ranges of invading organisms and identify the factors that promote its spread.

The research conducted by the university has led to the development of the first multi-scale and multi-factor model that evaluates the potential regional and global reach of the bacteria, which is very harmful to olive trees.

The study also identified the regions with the highest risk of exposure to the bacteria, which include the south of Brazil and the United States, Central America and southern Europe.

See Also:Xylella fastidiosa NewsAccording to the models, Australia and southern Africa are two areas where Xylella may also arrive. Zones beyond latitudes of 40 to 50 degrees appeared to be at a lower risk.

The rapid spread of Xylella and the serious damages it has caused to Italian olive groves is causing concern among producers around the olive oil world. Many are worried that the continued spread of the disease will have a potentially catastrophic impact on the global olive and olive oil industries.

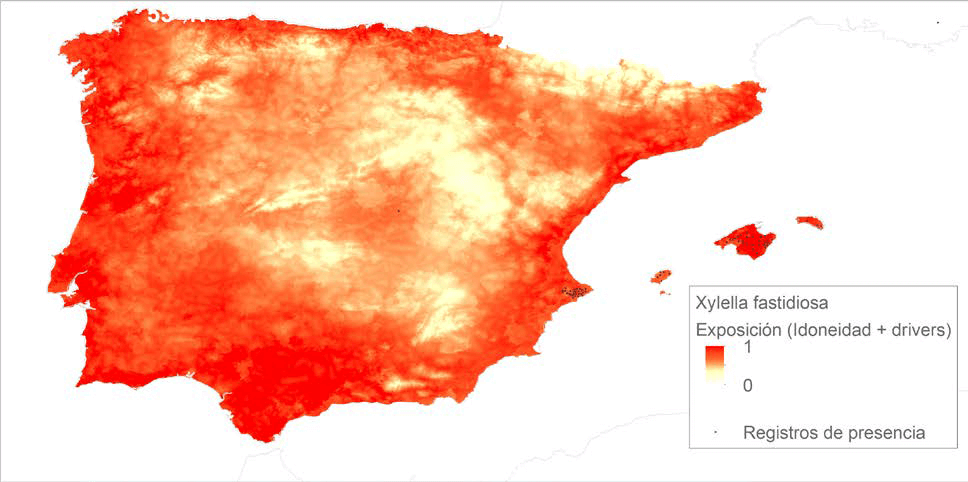

In Spain, in particular, the study showed that the Iberian Peninsula is at particularly high risk to the entrance and spread of Xylella, which is already widespread in the Balearic Islands. The models identified the Mediterranean coast and the southwest of Spain, with high temperatures and a lot of rain in winter, as the areas at the highest risk.

The study also showed numerous similarities of the parts of Spain with the highest risk of contracting and propagating Xylella. These included each location’s proximity to coastal zones where agriculture is very present, their intermediate population densities, which are well connected.

Areas with a lower risk were located in the interior of the peninsula and had an intermediate population density.

The map is the first of its kind due to the incorporation of ecological niche models, which analyzed the relationship between registries of current Xylella cases and bioclimatic data that evaluated 19 variables related to temperature and rainfall.

Prior to this research Xylella fastidiosa’s global distribution models had been developed based on the extrapolation of very specific regional data.

Oliver Gutiérrez Hernández, a professor at the University of Málaga’s geography department and Luis García, from Spain’s National Research Council, argued in the study that in order to properly examine the scope for the spread of Xylella, more data than was used in previous studies had to be taken into account.

“In the Anthropocene, geography plays a crucial role in the management of biological risks,” the pair wrote. “The success in the management of them depends, to a large extent, on our ability to predict the potential geographic ranges of invading organisms and identify the factors that promote its spread.”

However, Gutiérrez Hernández and García also acknowledged that the study and model they have constructed have several limits, including that data has only been taken from areas where Xylella is known to be present. This means data from areas where the disease may also be viable but has not yet been detected has been left out.

The unpredictability of human interaction with the disease can also not be completely accounted for in the models.

“Ecological niche models based on bioclimatic data underestimate the potential distribution when the human beings intervene as a vector of the species,” Gutiérrez Hernández and García wrote.