Infographics and so-called “interactives” aim to present complicated subjects with aesthetic simplicity. All too often, though, their beauty comes at a cost. Like the informational limitations of the 140-character Twitter update, these swipeable cartoons leave readers with an incomplete and often inaccurate understanding of topics that deserve a closer look.

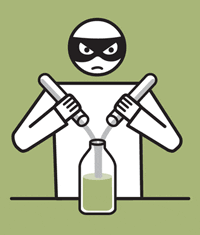

Yesterday, the New York Times offered a slideshow titled “Extra Virgin Suicide,” that presented 15 cards on the process of large-scale adulteration in the olive oil industry in Italy.

See Also:NY Times Olive Oil Fraud Infographic TimelineHours after it was published, I asked four people at a dinner party to swipe through the Times piece on my phone and tell me what they thought the “takeaway” of the feature was. This was what they said:

- “Don’t buy Italian olive oil.”

- “Everyone in the olive oil business is a crook.”

- “Makes me want to use another oil, like grapeseed.”

- “I had no idea most olive oil is cut with chemicals. It makes me sick.”

Although the second slide of the presentation contains the critical qualifier “much” Italian olive oil, some readers were left with the impression that all Italian producers work this way.

One of the cards in the series said, “approximately 69 percent of the olive oil for sale in the U.S. is doctored.” It presumably referred to the 2010 UC Davis study that found samples of ten imported brands labeled extra virgin in three California supermarkets (not exactly a national sampling) to be substandard — not that they were intentionally “doctored.”

The article cites “Extra Virginity” author Tom Mueller as its source.

The Times applies a loose definition to the term “interactive,” apparently referring to how we get to click from one slide to the next and back if we want. There is no way for readers to actually comment on the piece (and there certainly would be comments).

Over the past few years, bewildered consumers have been bombarded by confusing messages from olive oil evangelists and negative campaigns by groups of producers in their zealous pursuit of market share.

Simple, informative messages about olive oil quality, benefits and uses will eventually clear the confusion and foster greater consumption of this vital, healthy food.

However, in efforts to boil down such a complicated topic for increasingly short attention spans, there is the danger that oversimplification can disguise what is often just more misinformation.

The New York Times Olive Oil Fraud Infographic Timeline

Jan. 26, 2014 10:20 UTC

Jan. 26, 2014 10:20 UTC Curtis Cord

Curtis Cord