Spain’s Sea of Olives UNESCO Application Moves Forward

Nearly 140,000 hectares of privately- owned land will be excluded in a catalog, which was a sticking point for environmental lawyers and agricultural unions.

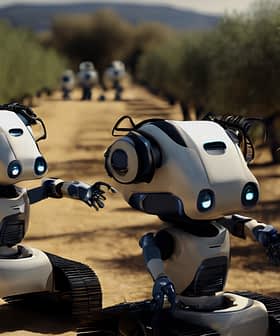

Sea of Olives, Jaén

Sea of Olives, Jaén After eight years of work from large parts of the Andalusian olive sector and public institutions, the application for UNESCO World Heritage List status for the autonomous community’s 1.3‑million-hectare Sea of Olives has been finalized.

Now, the massive olive grove landscape will be among the contenders to receive protected status from the United Nations at UNESCO’s July 2024 meeting. If the application is successful, the Sea of Olives will become Spain’s 49th or 50th World Heritage site, depending on the success of its 2023 submission.

The final sticking point in the application revolved around whether a 139,000-hectare section of privately-owned land included in the landscape first needed to be registered in the Andalusian Historical Heritage catalog before it could be included in the UNESCO application.

See Also:From Andalusia to Madrid, Spain Shocked at Wave of Olive TheftsA prominent Spanish environmental lawyer and three of the country’s most powerful agricultural unions argued that including the 139,000 hectares of private land would violate the property rights of the landowners and hamper their ability to grow olives profitably.

“The olive grove is the livelihood of many Andalusian families in rural environments where depopulation can become a real problem,” said Pilar Martínez Abogados, a law firm. “And a procedure like the one being considered can put your livelihood at risk.”

“It is evident that the first cost of conservation is to compensate and indemnify those who, for the benefit of the whole of society and to contribute to the defense of the public interest in the protection of nature, see the use of natural resources restricted to unimaginable limits their properties and their rights as owners,” the firm added.

However, a spokesperson for Spain’s Ministry of Culture and Sport told Olive Oil Times that other UNESCO World Heritage sites – including the Champagne area in France and the Prosecco area in Italy – still boast functioning vineyards, where producers profitably meet the criteria required of them by UNESCO while making wine.

Jaén’s Sea of Olives

The Sea of Olives is a nickname for the region of Jaén, Spain known for its vast expanses of olive groves. Jaén is the largest producer of olive oil in the world, and the olive tree has been a symbol of the region for centuries. The sea of olive trees in Jaén covers an area of approximately 600,000 hectares, and the landscape is dominated by the silver-green foliage of the olive trees, which stretch as far as the eye can see. The beauty of the Sea of Olives has been celebrated in literature and poetry, and it is a major tourist attraction in the region.

The spokesperson added that no compensation would be paid to farmers whose land was included in the proposed UNESCO site.

“It is not expected that this registration could interfere with their productive activity since this is part of the values that are to be protected,” the spokesperson said. “For this reason, there would be no room for compensation.”

Despite some lingering protests, the ministry, the Andalusian regional government and three agricultural unions reached a deal to exclude the privately-held olive groves, which spanned five provinces in Andalusia, from the catalog.

Francisco Reyes Martínez, the president of the province of Jaén and one of the most adamant supporters of the application, celebrated the agreement.

“The doubts that arose in the last meeting we held have been clarified thanks to the response from both the government of Spain and the Junta de Andalucía [the regional government] concerning the compulsory nature of registration in the catalog of Andalusian Historical Heritage,” he added.

The ministry and regional government justified the decision not to include the land in the catalog, stating that much of it is already located in protected areas and other similar schemes to preserve the cultural and historical value of the groves and mills.

“The objective of the convention is the patrimonial protection of the declared places, but always taking into account not only the benefit, but also the active participation of its population and its local communities, for whom this international recognition must be positive, and never be harmful,” the ministry spokesperson said.

“The legal protection that is applied will be aimed at safeguarding the patrimonial values of the place, among which is the physical maintenance of the landscape, but also the safeguarding of the intangible values linked to the tradition of the exploitation of the olive grove by human beings for centuries, millennia, techniques that have contributed to its perpetuation until today,” the spokesperson added.

The Sea of Olives, also known as the Andalusian Olive Landscape, stretches 200 kilometers from Jaén to Estepa, a town near Seville, and includes more than 180 million trees.

“There will be no impairment to the agricultural use of the olive farms,” confirmed Cristóbal Cano, the secretary-general of Spain’s Union of Small Farmers (UPA).

Along with the Association of Young Farmers and Ranchers (Asaja) and the Coordinator of Agriculture and Livestock Organizations (Coag), UPA was among the unions that previously opposed the application.