At the Accademia dei Georgofili in Florence, a March 11th conference gathered hundreds of intellectuals, political wonks, and agriculture buffs from across Italy to discuss some very old farming history. The school, which is the center for agricultural study in Italy, was celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Rivista di storia dell’agricoltura (Journal of the History of Agriculture) with a day dedicated to changes and continuities between ancient Roman times and the Middle Ages. Entitled “Agriculture and Environment through the Roman and Middle Ages”, the conference focused on the historical realities of this thousand-year period and its significance for today’s highly consequential balancing of farming and environment in Italy.

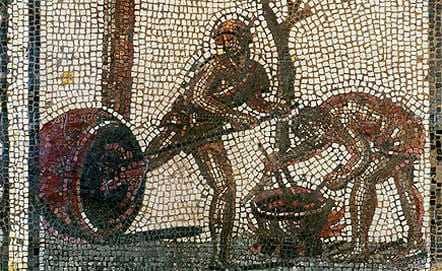

One of the most significant themes for all present was that of continuity — the presence of crops and even methods that began with the Romans and continued through the Middle Ages, and in some cases even up until today. The Romans of antiquity, immensely focused on cultivation and expansion of crops, introduced plants from the far corners of its empire and made them plentiful throughout the Mediterranean region and larger Europe.

With olive trees from Greece and grape vines from the Bordeaux and Bourgogne region of France, the Romans spread production of olive oil and wine throughout the continent, shaping cultures and cuisines for millenia. In Italy, especially in southern regions such as Puglia, many of the trees used to produce today’s olive oils date back a couple of thousand years and were planted by the Romans. The conference highlighted the ways that current farming culture is as much descended from the Roman and Middle Ages as is the artistic and social culture of Italy today.

However, the other theme of the conference was change — change generated by the environment and environmental change precipitated by agricultural practices. Sharp variations in food production, such as olive oil, had severe consequences at the end of the Roman Empire. As Paolo Nanni, Professor of Agriculture at the University of Florence, explained at the conference, “Suffice it to say that Rome, which was the largest city in the world, went from eight hundred thousand inhabitants to sixty thousand in the space of two hundred years, from the fourth to the sixth century.”

Italy remains a very pastoral country with rich agricultural activity, and the conference, while focused on a very distant age, was very much addressing the current age of agriculture and the threats to the environment. In foregone ages, first Rome and then the smaller central cities of the Middle Ages organized agriculture around them along pathways of transportation and communication, thereby leaving plenty of untouched forest and natural land.

With today’s ease of transportation, cities are no longer the hub of local trade and there are no limits on land-use. It is, as Paolo Nanni concluded, “doubly important that agriculture is done in a sustainable way, both economically and environmentally… and that the government recognizes the importance of the ecological strategy. This is why we held this conference.” As with so many of the modern problems of humanity, we look to antiquity for answers.