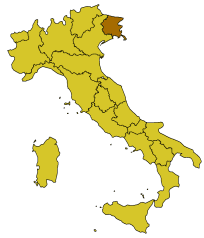

Friuli Venezia Giulia covers the northeastern corner of Italy, which borders Slovenia and Austria, and is just a stone’s throw away from the neighboring Croatian coast. “Clearly, this isn’t Tuscany or Puglia,” Franco Diacoli of Olio Ducale tells me, “we’re in the most extreme northern region where it is still possible to cultivate olive trees, but in many ways this extremity produces an oil with very intense characteristics, aromas and flavors.”

The Bianchera olive variety hails from the province of Trieste, where the warm sea breeze mitigates the climate and keeps the olives safe from freezing winter temperatures. The pianura — plain – is tucked under the hills where strong winds from the north carry away the humidity. “It’s always well ventilated in this area, and this is in favor of the cultivation of olives, because humidity carries the freeze,” Diacoli explains.

In 1929, the Bassa Friulana suffered a frost which left almost all of the region’s olive groves destroyed. “Olives need sgrondi terrain made of ghiaioso – well drained and gritty — not humid in the earth or in the air.” Where the earth is made of gravel and rock it retains less water and the olives suffer almost no damages at all in the event of a frost.

In 1929, the Bassa Friulana suffered a frost which left almost all of the region’s olive groves destroyed. “Olives need sgrondi terrain made of ghiaioso – well drained and gritty — not humid in the earth or in the air.” Where the earth is made of gravel and rock it retains less water and the olives suffer almost no damages at all in the event of a frost.

This year Franco Diacoli was lucky; on the evening of December 19th, 2009, the temperature dropped from 8 to 10 degrees Celsius during the day to ‑12 degrees Celsius overnight. In the region of Cividale del Friuli where Diacoli cultivates 7 to 8 varieties of olives, the land is more gravel than terra, or earth, therefore his olives were mostly saved.

Apart from the Bianchera and a few other autochthonous varieties, Diacoli also cultivates Tuscan varieties such as Frantoio, Leccino, and Maurino, because the microclimate of Tuscany is very similar to that of Cividale del Friuli with respect to the rainfall and temperature. “Clearly we can’t grow varieties from Sicily in Friuli, because the differences in climate are too extreme.

Our quantity may not be that of Puglia, for example,” Diacoli points out, “however, from June to September it never rains there, so the olives stop growing until the rain starts again. Here in Cividale, we always get rain, so our olives never stop growing and developing intense flavors and aromas.”

Our quantity may not be that of Puglia, for example,” Diacoli points out, “however, from June to September it never rains there, so the olives stop growing until the rain starts again. Here in Cividale, we always get rain, so our olives never stop growing and developing intense flavors and aromas.”

The Bianchera olive produces a unique oil with primary characteristics of artichokes and herbs. It has a very low acidity level and very intense flavor, and for this reason it is often blended with other oils while staying true to the DOP certification parameters, or Denominazione di Origine Protetta, which regulates the quality and territory from which the oil comes, and protects the olive oil consumer. However, Diacoli makes an extra virgin olive oil using 100% Bianchera that, he points out, placed among the top 10 out of 220 olive oils at a recent event in Croatia.

“Apart from the Bianchera which I produce and, like they say, la campanile di casa e sempre piu grande, — the bell tower of your home is always the largest — the flavors and aromas of Sicilian olive oils are the best in my opinion. They have particular sensations of tomatoes — the leaf and the fruit.” However, Diacoli admits, “It always depends on the quality of the olives, the land from which they came, and how the oil was produced; you can have terrible olive oil from the same place where beautiful oil is made.”

“Apart from the Bianchera which I produce and, like they say, la campanile di casa e sempre piu grande, — the bell tower of your home is always the largest — the flavors and aromas of Sicilian olive oils are the best in my opinion. They have particular sensations of tomatoes — the leaf and the fruit.” However, Diacoli admits, “It always depends on the quality of the olives, the land from which they came, and how the oil was produced; you can have terrible olive oil from the same place where beautiful oil is made.”

In the north, it is typical to harvest the olives while they’re still green, before they’ve matured, because once the ground has frozen it’s too late to produce an oil of good quality. “We harvest in very late November, before the olives turn black — this gives us intense flavors and aromas,” says Diacoli. “We can’t think of harvesting in February, as they do in the south. In Puglia and Sicily they often harvest the olives when they’re very mature, they even let them fall from the tree. So the percentage of oil is more, but the quality can be less.”

“In order to make a good product, it’s important to follow strict guidelines; you have to bring the healthy olives to the press once they’ve matured to the perfect point — you can’t wait for the olive to become overripe, they should be half green and half dark; at this point the olives don’t contain the maximum amount of oil, but they have the maximum aromas and flavors. Then you need to harvest and press in the same day, which takes some coordination.”

Diacoli harvests his olives by hand and takes them to a public press used by other olive oil producers in the province of Cividale. “I have to stick to a schedule; I have to make an appointment to bring my olives to the press at a certain time, but not first thing in the morning — if the press has been sitting overnight with the pulp from another farm, I don’t want that oxidized pulp mixing with my olives and deteriorating the quality of my oil.”

Diacoli began cultivating olives 9 years ago when a friend offered him a piece of land from his farm. “It happened by chance; the farmer who was working this piece of land had quit, and my friend didn’t know what to do with it — he has a large farm, so it was nothing for him to invest a little something in a new project. We decided to plant some olive trees and when it was time, we’d harvest the olives. We didn’t have a clue about how to make olive oil, but this was our idea.”

They had some help from ERSA, Ente Regionale di Sviluppo Agricolo, the agency for the rural development in the region. “They gave us a hand, told us how many trees to plant on this piece of land, how far apart, and what we’d need to go about making the olive oil,” says Diacoli. Over the years, Diacoli has discovered the passion and dedication it takes to cultivate and harvest olives, and produce a high quality olive oil. “When you taste a good olive oil, it shouldn’t dirty your mouth. The flavors should be intense and persistent, they should linger, but the olive oil should leave your mouth clean. If it leaves a greasy film on your tongue, then you know something went wrong during the production process.”

When it comes to selecting extra virgin olive oil in a supermarket or specialty store, Diacoli advises, “It’s not true that the price makes the quality; it’s the opposite. If anything, the quality makes the price.”

So why buy an olive oil that hails from Friuli, a region better known for it’s wonderfully crisp white wines and picturesque views of the Alps? “In all typical products, there is the terroir. I like to give this example: In Friulano olive oil there are the characteristics of amaro e piccante, bitter and spicy, of the Bianchera olive, which are quite strong and intense. Come la persona, just like a Friulano, with respect to our typical characteristics; we are tosto, ruvido, grezzo – tough, coarse, and raw — we’re not very expansive as a people. Over the years we’ve endured many barbaric invasions and massacres in this region, and we’ve become closed and distrustful towards strangers. But when a Friulano manages to put their trust in another, it becomes the contrary; we are more affable than all the others.”

“Surely, Italians from the south are more open and accommodating from the beginning — like the Napolitani. Their olive oils are also sweeter — the bitter elements hardly exist at all. This comes from tradition, from a way of thinking. I’ll explain: If I harvest 100 kilos of olives and leave them in the sun to dry out, when I put them on the scale I’ll have 60 kilos of olives, but the same amount of oil either way. What has happened? When I take the olives to the press, I have to pay by weight, not by the olive oil I produce. When the economy was in bad shape, it became a habit for people to leave their olives out in the sun to dry. This produced an oil of lesser quality — it was still an olive oil that had fat and gave energy, but the cost was cut almost in half.”

“This mentality still exists in the south; not everyone, mostly old families have continued the tradition of drying their olives out in the sun before going to the press. Sometimes they even wait to harvest the olives until after they’ve fallen from the tree. This is the problem with oil of bad quality; to make an olive oil of good quality, the olives must be harvested before complete maturation. We lose a bit in the oil, it costs us at the press, but in the end we have an important oil,” says Diacoli. “I gave my olive oil to some people from the south to taste, and they said that the oil from this region is no good — it’s raw.”

When asked if he is looking to produce the same tastes and aromas with each harvest, like a wine maker, Diacoli replied, “No. With olive oil you can’t change anything. You can screw up, make a mistake, and ruin it. But, if you do everything well, it can be wonderful, because your trees had water, sun, etc. Or it can be a bit less, because it was a dry year, or who knows. With wine, you take it into the cantina, and you work it — with olive oil you can’t do anything. What the press gives you is what you get.”

With respect to Diacoli’s prized Bianchera, he says, “It’s very difficult to cultivate, because it’s a variety that’s susceptible to a fungus known as, l’occhio di pavone, that attacks the leaves of the tree.” Yet ultimately, “It gives us an exceptional olive oil, and — like most things in life — it’s the things that are most difficult that are almost always most appreciated.”

Photos: Lara Camozzo for Olive Oil Times