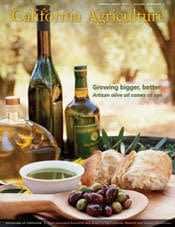

Sparked by huge changes in the California olive industry in recent years, California Agriculture magazine devoted a special issue, “Growing bigger, better: Artisan olive oil comes of age,” to this industry which has set a substantial foundation for future growth and profitability. “We thought it was a good topic for us,” said managing editor, Janet Byron. “I’ve been here twelve years and we’ve had very little with olives, specifically olives grown for oil which is new to California.” The goal of the quarterly, peer-reviewed journal which reports research reviews from the University of California and its Agriculture and Natural Resources division is to “take the science and translate it into an accessible form,” explains Byron. “We love pulling together a package of articles that will be useful to people.” The issue presents a series of articles that examines the impact of the recently certified sensory taste panel, the nonnative, invasive fruit fly, and super high density plantings.

Sensory Panel

“UC Cooperative Extension sensory analysis panel enhances the quality of California olive oil,” written by Paul M. Vossen, UC Cooperative Extension and Alexandra Kicenik Devarenne, writer and educator examines the role of the sensory analysis panel in the state’s olive oil industry. The last two decades have marked the revival of California olive oil with production at an all time high and predicted to double in the next few years from 800,000 to 1.6 million gallons. Many California olive oils have earned recognition for their excellence in both domestic and global competitions. The quality of the oils is largely due to the sensory analysis panel. “Only the most rudimentary quality testing on olive oil is currently being done by laboratory chemical analysis; a group of human beings following strict tasting protocols is now the standard tool for detecting, identifying and quantifying the many positive and negative attributes of olive oil.”

“UC Cooperative Extension sensory analysis panel enhances the quality of California olive oil,” written by Paul M. Vossen, UC Cooperative Extension and Alexandra Kicenik Devarenne, writer and educator examines the role of the sensory analysis panel in the state’s olive oil industry. The last two decades have marked the revival of California olive oil with production at an all time high and predicted to double in the next few years from 800,000 to 1.6 million gallons. Many California olive oils have earned recognition for their excellence in both domestic and global competitions. The quality of the oils is largely due to the sensory analysis panel. “Only the most rudimentary quality testing on olive oil is currently being done by laboratory chemical analysis; a group of human beings following strict tasting protocols is now the standard tool for detecting, identifying and quantifying the many positive and negative attributes of olive oil.”

The article explains how sensory analysis of olive oil, which took root in the late 1980s, now plays a key role in how olives are rated for market grade, helping growers and processors produce a higher quality product. Sensory evaluation is also used to “characterize olive oil flavors attributable to cultivar (variety), fruit maturity, terroir, irrigation, tree nutrition, pest damage, fruit handling and processing methods.”

A trained sensory panel provides an objective evaluation of olive oil that can be used to “enforce label standards that protect consumers, producers, and processors from fraud in the industry.” The International Olive Council standards for extra virgin and virgin are globally recognized.

Olive Fruit Fly

Three articles delve into the olive fruit fly (Bactrocera oleae), which plagues olives worldwide and was first detected in California in 1998 in the Los Angeles Basin. “Understanding the seasonal and reproductive biology of olive fruit fly is critical to its management” explains that while the table olive can’t tolerate damaged fruit, infestation levels of 10% or more may be fine for olive oil, especially if the olives are processed quickly. The impact is especially clear in Butte County whose high fly densities resulted in crop rejection by table olive processors. Olives grown in Butte are now crushed for oil and are increasingly super-high-density plantings, which seem to be less conducive to olive fruit fly infestation.

In order to predict where and when the fly would most likely become a significant pest, UC researchers and Cooperative Extension farm advisors, California Department of Food and Agriculture Pest Detection and Emergency Project personnel, county agricultural commissioners and pest control advisers set up monitoring sites throughout the state in 2002. Data was collected from a total of 28 sites in 16 counties between 2002 and 2006.

As a result of this data, researchers are producing models determining when olives are most susceptible to fruit fly attack and how fly populations respond to climatic conditions. The work will continue to develop tools to further apply this information toward more effectively managing the olive fruit fly.

Given the limitations of insecticide-based programs, and the number of residential and roadside olive trees, the next article, “Biological controls investigated to aid management of olive fruit fly in California,” discusses how biological control — the importation of natural enemies — has potential to suppress olive fruit fly populations. California scientists have documented the natural enemies of the olive fruit fly with the intention of importing them from other countries and then determining the effectiveness and limitations of the introduced species. The release of several parasitoid species have been approved by the U. S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS) with permits pending on two others.

The benefits appear to outweigh the risks of the release of natural enemy species that non-target species may be attacked. The importance of biological control is growing in regions where pesticide use is less desirable or restricted.

California’s Central Valley is known for its blazing hot summers. “High temperature affects olive fruit fly populations in California’s Central Valley” shares results of field studies of the Valley’s olives, which are commonly infested by the olive fruit fly and show lower trap counts during the mid and late months before they pick up again from September to November when temperatures are cooler. The flies rely on adequate water and carbohydrate supply to fly and reproduce.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) maps may be useful for growers and consultants to determine if they can temporarily stop insecticide treatments during periods in July and August. But, it should be warranted that factors other than temperature influence the likelihood of the fruit fly being a problem in a particular orchard such as local water sources or even morning dew. On the flip side, following these maps will help indicate the region’s history of low temperatures that are conducive to fruit fly activity and survival in a particular area. In addition, understanding the dependence of the fruit fly on water and carbohydrate during high temperatures can help determine the best ways to bait the pests in the effort toward olive fruit fly control.

Super High Density

The early 1990s introduction of the super high density (SHD) hedgerow system for olive orchards meant decreased production costs while maintaining high quality. Two articles are devoted to this system. The first, “Mediterranean clonal selections evaluated for modern hedgerow olive oil production in Spain” explains that the mechanical harvesting machines are most efficient when tree size is limited, making a cultivar adapted to this system desirable. Three cultivars: ‘Arbequina i‑18’, ‘Arbosana i‑43’ and ‘Koroneiki i‑38 were field tested by the Institut de Recerca i Tecnologia Agroalimentaria (IRTA) in an irrigated, SHD planting system in northeast Spain.

Scientists at IRTA are “evaluating additional clonal materials and old orchards of olive varieties, and prioritizing the search for varietal characteristics that can improve productivity, a low vigor/compact growth habit, disease resistance and extra-virgin olive oil with high levels of antioxidants.” California’s SHD orchards will soon be able to compare its experiences with other regions in extra virgin oil quality, economic viability, orchard management and sustainability and natural resource utilization.

With the rising worldwide olive oil consumption, many countries are increasing their olive acreages. The traditional production systems of the Mediterranean are hundreds of years old with low yields and high production costs. The authors of “Olive cultivars field-tested in super-high-density system in southern Italy” believe super high density olive culture may be the answer to help increase profitability in Europe as well as the U.S.

The experimental orchard was begun in the summer of 2006 in Valenzano, Italy with Arbequina, Arbosana, Koroneiki, Coratina, and Urano cultivars. The results were as expected: “In terms of early bearing and yield consistency, all the tested cultivars performed satisfactorily. And in sensory evaluations, the resulting extra-virgin oils had sweet typology and were well-balanced, highly fruity and ready to use.”