Portugal May Be the Third-largest Olive Oil Producer by 2030

Investments in high-density groves and modern mills are driving Portugal's rise among olive oil producers.

Esporao

EsporaoPortugal has the potential to be the third-largest producer of olive oil in the next ten years, according to a study presented last month.

Alentejo: Leading the International Modern Olive Industry was presented at the sixth edition of Olivum days. In the 107-page report, researchers from Consulai and Juan Vilar Strategic Consultants said modern, high-density groves and investments in technology are paving the way for the country’s rise among olive oil producers.

“With the expected growth over the next ten years, Portugal will be the largest reference in modern and efficient olive growing in the world, and possibly the seventh-largest in surface area, and the third-largest in world olive oil production,” the authors of the study wrote.

Portuguese olive groves have undergone a profound transformation from a traditional and non-competitive to a modern and efficient.

Portugal is currently the world’s ninth-largest producer of olive oil. This year, producers in the country are expecting a record-harvest of 140,000 tons.

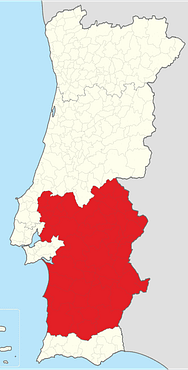

Leading the way in Portugal’s charge to the top is the southern region of Alentejo.

Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Spanish border, Alentejo takes up roughly a quarter of the country’s landmass and is responsible for slightly more than three-quarters of all Portugal’s olive oil production.

See Also:Olive Oil Production News“[In the last 20 years,] Portuguese olive groves have undergone a profound transformation: from a traditional and non-competitive olive grove to a modern and efficient olive grove,” the authors of the study wrote. “Alentejo led the current transformation of international olive growing.”

Back in 1999, 98 percent of olive groves in Alentejo were traditional. The olive trees in traditional groves are more spaced out than in intensive or super-intensive groves and machines are not used to harvest the fruits.

Traditional producers in the region tend to have fewer than 250 trees per acre, while super-intensive producers usually have at least 1,000.

The average yield from traditional groves in Alentejo was about 7.5 tons per acre. However, in the super-intensive groves, yields were between 24.7 and 29.7 tons per acre. This caused annual production in the province to increase by more than 1,000 percent in less than 20 years, rising from 8,534 tons in 1999 to 97,004 tons in 2017.

Super-intensive groves now make up about 63 percent of all olive groves in Portugal. As more groves are converted from traditional to super-intensive, Portugal’s olive oil production is forecast to continue climbing.

“Over the last few years we have seen a very strong evolution of olive grove productivity in Alentejo,” the researchers wrote. “However, it is expected that current levels of olive productivity in the Alentejo can continue to increase as traditional olive groves are converted.”

Part of what has led to this production boom was the construction of the Alqueva dam, which has allowed super-intensive groves to proliferate. Prior to the construction of the dam, only traditional groves could survive in the region due to the prevalence of drought and wildfires.

Another driving factor has been the modernization of the country’s olive oil mills. As olive oil yields have continued to trend upwards, the number of mills in Portugal has steadily declined. Small traditional mills have quickly been replaced by larger, more modern ones.

“The region has invested in modern and efficient production processes which have significantly increased productivity, and invested in the installation of oil mills that are some of the most developed in the world,” the researchers wrote. “This has allowed Portugal to significantly improve the quality of its olive oils.”

Alentejo

The researchers also highlighted how the modernization and investment in Alentejo and Portugals’ olive groves have benefited the country’s economy. In the last three years, olive oil production in Portugal has generated a turnover of €620 million ($690 million), which is 2.5 times higher than the turnover recorded between 2010 and 2012.

Portugal’s olive oil exports have also grown rapidly and the researchers believe this trend will continue as more investments are made in high-density groves and modern mills. In 2017, Portugal exported €500 million ($555 million) of olive oil, making it the fifth-largest exporter of the product by value.

Overall, earnings from olive oil now make up nine percent of the value of all of Portugal’s annual agricultural production.

The researchers also said that the growth of the sector has created steady employment and investment in both Alentejo as well as the rest of Portugal, something that had been severely lacking prior to the construction of the Alqueva dam.

However, not everyone is celebrating the meteoric rise of Portugal’s olive oil production. Many traditional farmers, who either cannot afford to invest in super-intensive groves or do not want to, say their oils are being outcompeted and, as a result, their way of life is slowly beginning to disappear.

“Some old farmers are abandoning their olive groves because they don’t earn enough to produce the olives in the old groves,” Ana Carrilho, a local olive oil producer and the director of the Center for the Study and Promotion of Alentejo Olive Oils (CEPAAL), told Olive Oil Times. “Some of them have abandoned their groves, while others sell their land to the bigger companies.”

Carrilho added that since super-intensive groves operate with lower production costs per kilogram of oil produced, they can greatly reduce their prices; a luxury that traditional producers do not enjoy.

Still, the researchers and Carrilho believe that the modernization of Portugal’s olive groves will continue to benefit the entire sector, especially as locals begin to take the reigns.

“The Spanish were the main drivers of the first phase of modern olive groves in the region,” the researchers wrote. “[But] with the expansion of the Alqueva irrigation and the increased experience of those in the region, investment is now led by local entrepreneurs.”