Meet an Award-Winning Producer Promoting Greek Oils in Berlin

Amadeus Tzamouranis is connecting German consumers with olive oil producers in Kalamata.

Clara Marie Paul (back left), Amadeus Tzamouranis (back center) and Simone Artale (front) are the driving forces at Thalassa.

Clara Marie Paul (back left), Amadeus Tzamouranis (back center) and Simone Artale (front) are the driving forces at Thalassa. Butter has long been the edible fat of choice in Germany, with the European Union’s most populous country and largest economy among global butter production and consumption leaders.

However, olive oil consumption and culture have slowly gained a foothold in Germany. According to the International Olive Council, Germans consumed 76,900 tons of olive oil in the 2021/22 crop year, a 25 percent increase compared to one decade ago and a sevenfold increase compared to 30 years ago.

In Germany, there are many olive oils, but the problem is you don’t know who is behind the brand… We wanted to build a bridge directly from Greece to Germany.

While plenty of olive oil in Germany is purchased in supermarkets, Amadeus Tzamouranis is working to create a more intimate connection between Germans and extra virgin olive oil.

The chief executive of Thalassa (the Greek word for ‘the sea’), which produces the award-winning OEL brands, was born and raised in Berlin but spent his summers on the family’s olive farm in Kalamata on the Peloponnese peninsula.

See Also:Producer Profiles“I’ve always had a deep connection to Greece,” he told Olive Oil Times. “Although I knew olive oil, I never had the intense experience of being in the field, harvesting the olives, bringing them to the mill and seeing how the oil is produced.”

While olive oil was a ubiquitous part of his childhood, Tzamouranis said his first intimate experience came after getting a call from his uncle in 2015 asking him to come and help with the harvest.

Tzamouranis agreed and borrowed a friend’s van to drive from Berlin to southern Italy before crossing to the Peloponnese on a 24-hour-long ferry.

His original plan was to bring some paintings to his father, an artist hosting an exhibition, and medicine that was unavailable in the community. Tzamouranis also purchased some of his uncle’s olive oil to bring back to Germany and share with friends and family.

“I had this van full of paintings, medicine and all these things, and I didn’t have the idea to make a business out of it,” he said. “My idea was just to have a good time.”

However, this changed when he brought the freshly-harvested unfiltered extra virgin olive oil back to Germany.

Tzamouranis said unfiltered olive oil was a relative unknown in Berlin, but proved to be popular.

“I gave some to my friends, and they were amazed,” he said. “When it comes fresh, like two weeks old, most people in Germany don’t know this kind of taste because normally olive oil is stored and then filtered before being bottled.”

Soon one of his friends, who later became his business partner, recommended that he leverage his contacts in the German food industry – Tzamouranis had spent years working as a cook in Berlin restaurants – and start a business importing his uncle’s oil to fill the void of fresh, organic extra virgin olive oil.

“In Germany, there are many olive oils, but the problem is you don’t know who is behind the brand. There’s no connection to the producer,” he said. “We decided to make a brand from Berlin – OEL Berlin. We wanted to build a bridge directly from Greece to Germany.”

There have always been strong links between the two countries, with 2021 census data indicating that more than 450,000 Greeks live in Germany, the ninth-largest foreign national group in the country.

A separate 2019 report from Insete Intelligence found that Germans make up the largest share of tourists in Greece, with more than four million visiting each year, nearly 13 percent of total tourists, generating an average revenue of almost €3 million per annum.

“A lot of people here in Germany have a passion in general for Greece,” Tzamouranis said.

Despite these close cultural connections, he added that many Germany believed the old cliché that high-quality olive oil only comes from Italy and set out to change this.

At first, he imported the olive oil part-time, working up to three other jobs in parallel. After two years of this, he saved up enough to buy a small grove in Greece and returned to Kalamata to master the art of olive oil production.

Olive oil has long been a family affair for Tzamouranis, with formative experiences taking place in the olive grove with his grandparents.

“I wanted to learn everything,” he said. “I wanted to be there and not just be someone buying olive oil and reselling it.”

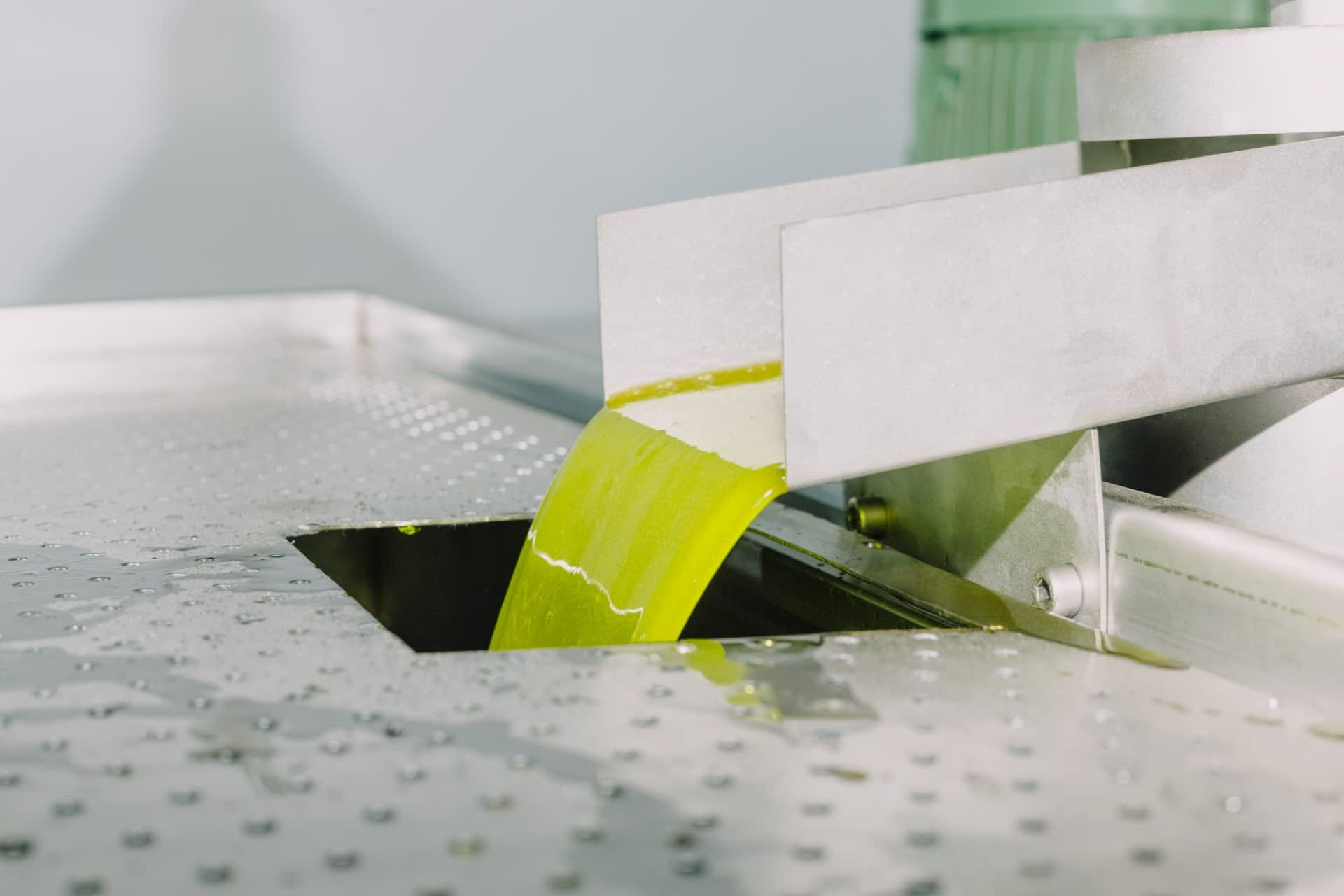

However, he soon found that he could not produce enough of his own olive oil to meet demand, so he went to Ilias Stavropoulos, who had long transformed his olives, and partnered with the certified organic miller of 30 years.

Now, Thalassa, the recently re-branded name of OEL, produces 100,000 liters of organic extra virgin olive oil each year, along with a range of other olive-based products.

“We are trying to give people an understanding of what needs to be done to produce a good olive oil,” Tzamouranis said, adding that many supermarket chains sell olive oil for €4 to €5, prices at which he could never afford to sell his oils.

Tzamouranis believes that extra virgin olive oil, the way he produces it, is a boutique and artisanal product that needs to be marketed and sold as such. To this end, he works closely with Berlin’s organic supermarkets and specialty food shops.

Working within the context of a retailer that already attracts a more significant portion of health-conscious clients has helped Tzamouranis to educate consumers about the health benefits of olive oil and how to use it in the kitchen.

“There are many customers who started using olive oil just for salads,” he said. “In Germany, there’s a different culture of how to use olive oil.”

As in many other non-olive-oil-producing countries, Tzamouranis said myths about frying with olive oil abound, as do misconceptions about cooking with olive oil. However, he added that this is slowly changing.

“I’m trying to find ways to inspire people on how to use olive oil with recipes,” he said. “It’s changing a bit. People are more aware that good olive oil needs to cost at least €15.”

The realization that producing quality products requires substantial investment has not come a moment too soon.

The harvest is set to begin in November, and Tzamouranis anticipates a good yield.

While Tzamouranis does not expect to begin harvesting until November, supply chain disruptions and inflation have created a challenging business environment.

He said the price of the tins in which he stores and sells his olive oil had “exploded,” and the costs of transportation and shipping from Greece to Germany had also risen significantly.

Additionally, his usual tin suppliers asked him to purchase a minimum of 100,000 units at a time, far more than he requires each harvest.

“We have higher costs, but we can’t pass these costs to the consumer because if we do that, who will buy our olive oil,” he said. “This is the problem we have, so we somehow need to find ways to deal with that.”

The company had been working on finding creative ways to add value to the extra virgin olive oil before the current macroeconomic difficulties emerged.

One way the company does this has been by focusing on the tin design. Tzamouranis said that adding the artistic dimension to the product helped the company to sell the oils in concept stores.

“We always try to focus on not only the quality but also the look,” he said. “We want people who buy our products because they like our design.”

Tzamouranis added that the focus on design increases the appeal of purchasing olive oil as a gift. “Olive oil is always a good present because you always need it,” he said. “You always use it, especially if it looks nice.”

The company also submits its olive oils to a range of competitions, including the 2022 NYIOOC World Olive Oil Competition, where its OEL Zoe brand, a delicate organic Koroneiki sourced from centenary and millenary trees, earned a Gold Award.

When all is said and done, Tzamouranis does not believe that any single producer is making the world’s best olive oil. However, he thinks that proving your quality provides value to customers, which is the business’s core component.

“I would not say that I’m making the best olive oil because many people are making good olive oils,” Tzamouranis concluded. “I’m trying to be authentic in what I’m doing, and I’m trying to give the people what they deserve.”