Peru Has Its Own Olive Council-Approved Tasting Panel

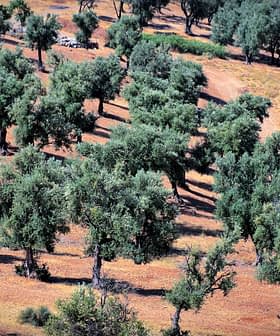

Peru celebrates the certification of its first International Olive Council-approved tasting panel in Tacna, aimed at improving olive oil quality and pursuing geographical indication certification. Producers hope the panel’s certification will enhance the value of exports, while also facing challenges such as the spread of the Mediterranean fruit fly in the region.

Producers and officials in Peru celebrated the certification of the country’s first International Olive Council-approved tasting panel ahead of what is expected to be a bumper harvest.

The 12-member panel was formed in Tacna, the country’s olive-growing capital, to help improve olive oil quality and aid in the region’s pursuit of a geographical indication certification.

There is also optimism that the credibility provided by an IOC-approved tasting panel certification will add value to individually packaged exports.

See Also:The Secrets to Successful Olive Oil Production in Peru“The tasting panel was identified as a need to support the production of quality olive oils in Peru and to somewhat close the innovation gaps that we had identified at the level of our region,” said Lourdes González, an award-winning producer at Vallesur and panel leader.

Previously, Peruvian producers had to send samples to neighboring Chile to be certified as extra virgin olive oil – which requires physiochemical and organoleptic testing – from an accredited tasting panel.

González said the widespread sensory analysis of Peruvian olive oil each year would also provide producers with feedback to fix any agronomic or milling problems known to lead to common defects.

She added that producers in Peru must improve quality to compete locally against imports and internationally at the higher end of the market.

“In Tacna, are we betting on a future Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) for olive oil,” she said. “We have identified characteristics that make a PDO certification appropriate. The panel will be a key tool in supporting this initiative.”

The panel formation also comes ahead of what González expects as a bumper crop in Peru.

After a hot winter that resulted in a historically poor harvest in 2024, she said conditions had been excellent ahead of the 2025 harvest.

“We had a normal winter with adequate temperatures, then there was an intense flowering phenomenon, and there was a good percentage of fruit set,” González said. “Consequently, this year’s production will exceed the average.”

However, Gianfranco Vargas, another producer near Tacna, warned about the continued spread of the Mediterranean fruit fly, the larvae of which feed on olives.

While the infestation has since come under control in neighboring Chile, Vargas indicated that the tripling of the number of hectares of fruit trees planted in southern Peru in the past 15 years has not been accompanied by an increase in resources for monitoring.

“Since we filed the complaint in Tacna, the number of fruit flies captured has increased monthly,” he said. “This increase had been dragging on since September of last year due to the increase in the hot season, which has accelerated the flies’ reproductive cycle.”

Officials in the region have responded by harvesting and burying overripe fruit that would otherwise be left to rot in the field and incubate future generations of the fly.

Despite these efforts, Vargas is skeptical that the National Service of Agrarian Health (Sensa) will meet its two to three-year target of eliminating the fruit fly in the region.