Researchers Use AI to Identify Extra Virgin Olive Oil Provenance

Researchers in Italy have developed a new method using artificial intelligence to determine the authenticity of extra virgin olive oil, specifically focusing on Taggiasca Ligure olive oil from Liguria. The method involves training AI to identify the origin of the olive oil based on its chemical compounds, with the goal of applying the methodology to other cultivars and regions to prevent fraud in the olive oil industry.

A new way to determine the authenticity of extra virgin olive oil has been devised by a group of researchers in Italy.

Their study, published by Food Chemistry, details a method that includes training artificial intelligence to identify the provenance of an extra virgin olive oil using its phenolic compounds and sterols.

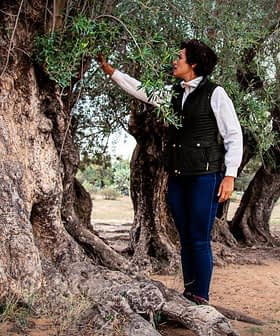

Researchers used Taggiasca Ligure extra virgin olive oil from Liguria in northwestern Italy.

“Still, the methodology we deployed could apply to any other extra virgin olive oil, to any cultivar, in any region,” Luigi Lucini, a researcher at the department for sustainable food processes at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore and co-author of the study, told Olive Oil Times.

See Also:Using Isotopic Footprints to Authenticate Olive Oil, Combat FraudThe main driver for the development was the spread of the Taggiasca olive, native to the region, to other countries. Therefore, the researchers felt it was important to be able to identify and label Taggiasca monovarietals from Liguria.

“I hear that the Taggiasca cultivar is being planted abroad, in places such as Greece,” Lucini said. “When we talk about wine, we are used to the concept of terroir. However, the link between extra virgin olive oil and the territory of origin is a real thing, and it implies specific quality characteristics.”

In the study, researchers said they could correctly identify locally-produced Taggiasca Ligure olive oils 100 percent of the time.

“We worked for four years on the project, and the last year was entirely spent training the system and verifying the efficiency of the method,” Lucini said.

The research team compared the new method to the FaceID authenticity tool widely adopted by smartphone producers.

“That system learns to recognize different angles of a specific face to authorize access to the device,” Lucini said. “Our method does the same; instead of somatic parameters, it recognizes chemical parameters, allowing it to authenticate the product’s origin.”

The researchers began the project by building a robust dataset using 408 samples of Taggiasca Ligure extra virgin olive oil collected from three harvest seasons. With the cooperation of local producer associations, they labeled every sample with coordinates.

Using metabolomics, the chemical fingerprint of a specific cellular process, researchers were also able to identify thousands of different compounds, dozens of which are unique to locally-produced Taggiasca Ligure olive oil.

“Cholesterol-derivatives and phenolics (tyrosols, oleuropeins, stilbenes, lignans, phenolic acids and flavonoids) were the best markers, based on statistics,” the researchers wrote. “Our results strengthen the concept of ‘terroir’ for extra virgin olive oil and indicate that profiling sterols and phenolics can support extra virgin olive oil integrity if adequate data treatments are adopted.”

“Extra virgin olive oil contents vary from season to season,” Lucini added. “Especially in Liguria, where you can find olive trees growing at sea level and others thriving at hundreds of meters only a few kilometers away.”

“Differences might also come from weather or farming techniques,” he said. “That is why we gathered data in different seasons to determine the exact markers we needed.”

See Also:European Geographical Indicators Valued at More Than $80 BillionOnce the data set was built, artificial neural networks were trained to identify Taggiasca Ligure extra virgin olive oils and deployed to determine the authenticity of oils labeled as such.

The researchers said the dataset should be flexible enough to identify whether locally-produced blends, including those claiming to comprise the Taggiasca olive, really do.

“Just like the FaceID tool, which recognizes me even if I have glasses on, our method does the same, and it is not obsolete when faced with olive oil blends,” Lucini said. “With FaceD, this happens because wearing glasses is not a determining parameter. The same is true of our method.”

To test the system, the researchers tested blended olive oil samples, where non-Taggiasca oils represented anywhere from 5 to 60 percent of the blend. Frantoio was one of the different olive oils used in the blends.

“The reason we chose the Frantoio cultivar is for the close similarity of its genetics with the Taggiasca cultivar, which is derived from the same olive tree as Frantoio,” Lucini said. “That is due to monks adopting the olive trees during the Middle Ages, with the cultivars evolving from there.”

“Both cultivars have a common ancestor, and if you use common genetics analyses, the two cultivars are virtually indistinguishable,” he added.

However, the researchers concluded that their artificial intelligence is ready to identify Taggiasca Ligure extra virgin olive oils outside laboratory settings. Now, the research team’s next steps will focus on wine.

“The reason is that we are trying to work on high added value products which can justify such demanding work,” Lucini said.

For this reason, the new method is mainly reserved for products with a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) or Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) certification from the European Union.

Italy boasts 49 extra virgin olive oils with a PDO or PGI certification, with several more candidates seeking with own geographical indicators in the coming years.

“Extra virgin olive oil is one of the foods more exposed to fraud,” said Marco Trevisan, the research coordinator and food chemistry professor at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore.

“And it is even more true for protected products, such as Taggiasca Ligure, on which consumers are willing to spend more money,” he concluded. “Our work… is a relevant step for protecting PDOs.”