Where the World's Olives Live Side by Side

From a distance, this olive grove on the outskirts of Córdoba looks just like any other field. But it is home for more than 1,000 olive cultivars from 29 countries, from Iran to the Americas, passing through all of the Mediterranean Basin.

IFAPA

IFAPAWalking through the lines of olive trees at the World Germplasm Bank is a fascinating introduction to the large, and often unacknowledged, diversity of olives.

From a distance, this olive grove at Alameda del Obispo, a facility of the Andalusian Institute of Agricultural and Fisheries Research and Training (IFAPA) on the outskirts of Córdoba, looks just like any other field.

Despite being an important crop and most of the commercial olive trees come from just a handful of cultivars, this species has managed to preserve a remarkable genetic diversity.

But a closer look reveals an astounding range of shapes and colors: from the small green Arbequina to the white Belica and the big and round Gordal olives.

This grove is home for more than 1,000 olive cultivars from 29 countries, from Iran to the Americas, passing through all of the Mediterranean Basin.

Olive trees from Syria, Turkey, Egypt, Albania, Croatia, Greece, Italy, Morocco, Argentina, the USA and Spain live side by side here.

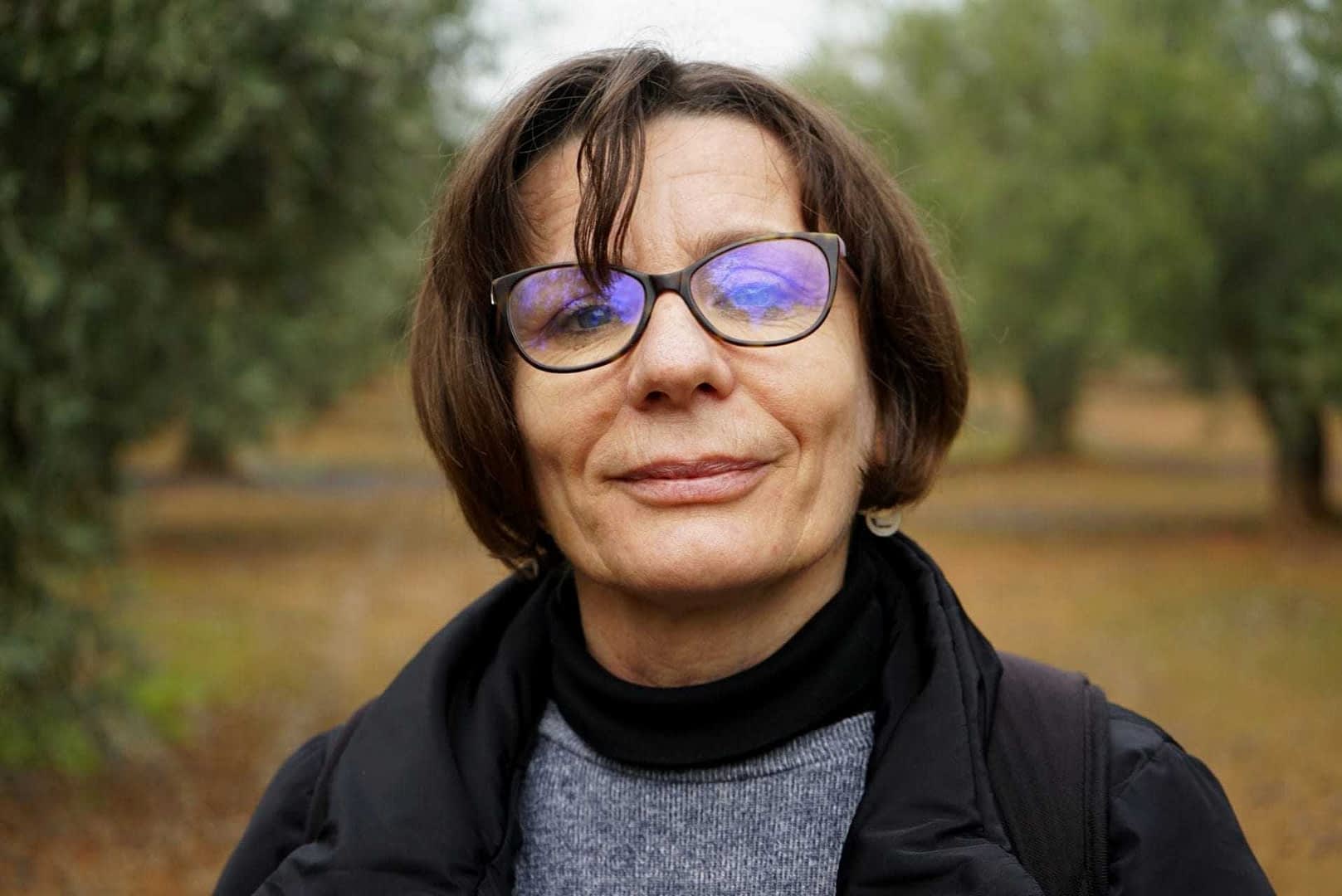

“Founded in 1972 by the Spanish Government with the collaboration of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and the International Olive Council, this is the oldest and largest international collection of olive trees cultivars in the world,” Angelina Belaj, director of the Germplasm Bank, tells Olive Oil Times.

The main goal of this collection, Belaj explains, is to gather and preserve the largest possible share of the genetic diversity of olive trees.

The germplasm bank grows two or three specimens of each cultivar in Córdoba and, in case something went wrong with this olive grove, they also keep a backup — a duplicate of it — in another estate the IFAPA runs in the province of Jaén.

“Despite being an important crop and most of the commercial olive trees come from just a handful of cultivars, this species has managed to preserve a remarkable genetic diversity. We believe that there are around 2,000 varieties worldwide,” says Belaj.

Some olive varieties can have different names in different countries, regions or even villages, so the first job of the scientist working here is to determine whether from a genetic perspective those names and origins hide known cultivars.

It’s a sort of detective work that often leads scientists to trace back the origin of cultivars whose expansion has sometimes been intimately linked with historical events and movements of populations across the Mediterranean throughout the centuries.

“It’s important to get to know the genetic part, but also the agronomic and morphologic part. It is useful as well to know the languages and history of the territories where the olives are grown,” Belaj points out.

“For instance, in Morocco, they have an important cultivar called Picholine Marrocaine, which from a genetic point of view is exactly the same as the one we call Cañivano Blanco in Andalusia. And it is also identical to an Algerian variety called Siwash.”

Angelina Belaj

“There have always been human migrations along the history and farming has never known of borders. Borders are very artificial and there has always been an interchange of knowledge and materials among countries,” Belaj adds.

Once the cultivars have been genetically identified and described from an agronomic point of view, the next question is: What can they be useful for?

In that regard, the World Germplasm Bank has become a key source of knowledge and materials for the scientists working at the program for the genetic improvement of olive trees — one of the main olive oil-related projects at IFAPA.

“The central aim of our improvement program is to obtain new cultivars that have high productivity and high oil yield,” Lorenzo León, researcher and coordinator of the program along with Raúl de la Rosa, tells Olive Oil Times.

Leon’s goal is to create new varieties that are able to produce high-quality olive oil while being able to adapt to different farming systems.

He and his colleagues mix existing varieties in order to get new ones with the traits they pursue.

One example of those new breeds is the recently created “Chiquitita” variety (and its sisters “Chiquitita 2” and “Chiquitita 3”), which combines the good qualities of Picual in terms of oil quality and productivity and the good features of Arbequina when it comes to adaptability to hedge plantations.

“In the last few years, there has been an increasing number of high-density hedge plantations. However, there are just a few available varieties that can adapt to that system. Hence, one of our aims is to obtain new cultivars that can perfectly adapt to that high-density hedge plantation system,” León explains.

Another research field for León and his team at IFAPA consists of obtaining cultivars that are resistant to diseases affecting olive trees.

“We have sent material to Italy and the Balearic Islands to evaluate the resistance to the Xylella [fastidiosa],” Belaj says. “We are also working in improvement lines such as the resistance to Verticillium wilt.”

Caused by a fungus, Verticillium wilt is one of the most widespread olive tree diseases. It interrupts and reduces the water movement from the roots to the leaves and may lead to leaf and fruit drops.

“The problem is that most of the grown cultivars nowadays are very vulnerable to this disease. And those that are a little more resistant are not interesting from an agronomic point of view. With the improvement program we want to unite these two qualities in new cultivars,” says Alicia Serrano, a researcher at IFAPA.

Taking the results of their work out of the research world and making them understandable and appealing to farmers — who are often very attached to their traditional cultivars and farming techniques — is one of the main challenges for scientists developing new olive cultivars.

León admits that step may take time, but he is optimistic.

“I think that the genetic improvement is not about to fight against traditional farming, but about offering new alternatives,” he says.

“It’s obvious that through these works of genetic improvement we are getting new materials which may offer good alternatives for the future of farming,” he concludes.