A pair of Italian food scientists and nutrition researchers have reiterated their belief that Nutri-Score does not provide the most accurate reflection of certain food’s nutritional value.

Italian detractors of Nutri-Score, including the minister of agriculture, Teresa Bellanova, have criticized the French-backed front-of-pack labeling system as overly simplistic and believe it should not be adopted by the European Union.

(Nutri-Score) is wrong. It is the fear of one specific macronutrient, fat in this case, that annihilates all of the other characteristics of that food.

Despite the opposition, Nutri-Score has been steadily gaining traction in northern and western Europe and has already been adopted by several large food production companies and several studies have come out in support of its adoption by the 27-member bloc.

However, a pair of Italian food science and nutrition experts told Olive Oil Times that those in favor of adopting Nutri-Score should more carefully consider the consequences of having such a simple and potentially “misleading” pan-European labeling system.

See Also:Seven Countries Protest Adoption of Nutri-Score at European Meeting“The Nutri-Score message – five categories, five letters and five colors – constitutes a misleading simplification,” said Francesco Capozzi, a professor at the agricultural and food sciences department of the University of Bologna and co-founder of the Foodomics discipline.

“We have been working to let the consumer receive adequate food education. Do we really have to begin treating our citizens like children?” he asked.

“Nutri-Score is a very arbitrary system that takes into consideration several known parameters, considering some negative and some positive, and gets a score out of them,” added Luca Piretta, a gastroenterologist and professor of food science and human nutrition at the University Campus Biomedico in Rome.

“This brings us to misleading results, where calories, fats or proteins are counted arbitrarily and used to produce colors and labels to classify food,” he added.

Capozzi noted that the current E.U. regulation 1169/11 already provides consumers with all the information that they need to make an informed decision when comparing food items.

“When someone buys some type of food, it is not because the consumers trust advertising, it happens because there is a contract between seller and buyer,” he said. “As a consumer, I can count on the fact that a truthful list of meaningful contents must be published on the package.”

“Oversimplifying nutritional information to the point that it becomes inaccurate represents a violation of that regulation,” Capozzi added. “What counts is the message the consumers receive. It is not only damaging to the consumers’ freedom of choice, but also to food science and nutrition.”

“The quantities of energy, fats or macro nutrients are a relevant part of food content, but food is also made of many other components,” he continued.

Capozzi also argued that Nutri-Score does not reflect an accurate snapshot of a food’s healthful qualities because the algorithm classifies food on the basis of a standardized quantity, such as 100 grams or 100 milliliters.

In the case of a food item such as extra virgin olive oil, which receives a C‑grade from Nutri-Score due to its fat content, the aforementioned quantities do not reflect realistic consumption levels.

“No one will ever eat 100 milliliters of olive oil while dining. Maybe some could eat 100 grams of oats, but in just a small spoon of extra virgin olive oil we find polyphenols and many other compounds which are essential for our own health,” Capozzi said.

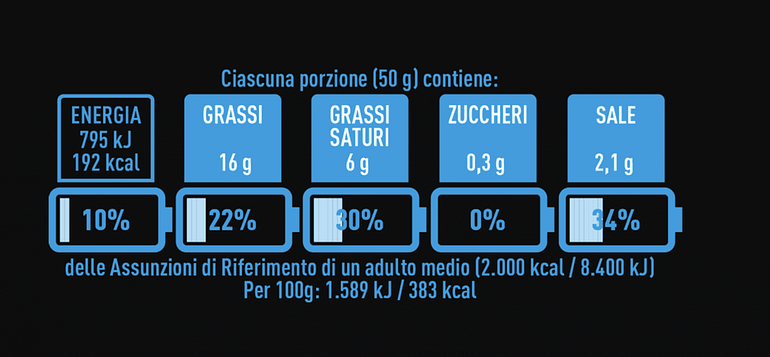

“If we consider the alternative labeling system proposed by the Italian government, the Nutrinform Battery, we enter a totally different field, one that focuses on educating consumers while not manipulating their choices,” Piretta added.

According to the specialist, the argument between which front-of-pack labeling system is best comes down to a cultural divide.

“There is no such thing as a bad food or a good food, there is no such thing as a food that can be eaten and one that cannot,” he said. “We need to focus on the quantities as related to the overall food and nutritional daily intake.”

Piretta agreed with Capozzi that the way in which Nutri-Score compares the nutritional content of food is inadequate to capture the health benefits associated with extra virgin olive oil.

“[Nutri-Score] is wrong,” Piretta said. “It is the fear of one specific macronutrient — fat in this case — that annihilates all of the other characteristics of that food.”

“That also happens with hard cheese, which gets low scores from Nutri-Score because of the 100 grams quantity standard,” he added. “Portions of food should be taken into consideration. In a Nutri-Score environment, we could even find sugar-free carbonated drinks that rank better than olive oil because, once again, not all of their contents are considered,” since they are packaged in containers far larger than the standard 100-milliliter measurement used by Nutri-Score.

The two experts believe that if a product is labeled with the warning colors and low scores employed by Nutri-Score, consumers will simply select foods labeled with an A or B grade and ignore the contents of the item.

“The traffic light system in Nutri-Score is simple, yet complex things cannot always be made simple,” Piretta said. “Food education requires time.”

Piretta and Capozzi believe that if a labeling system is to be introduced, it should be used to value the balance among the different products’ average intake.

On the other hand, supporters of Nutri-Score believe that consumers make comparisons among products of the same category.

They argue that, for example, the simplified label allows consumers to more easily determine that extra virgin olive oil – graded with a “C” – is healthier than other common cooking oils, such as palm oil, which is graded as an “E.”

However, Nutri-Score detractors do not believe that consumers will interpret the system’s grades in such a nuanced fashion.

“The consumer will not buy a product labeled C, simply because it is labeled that way,” Piretta rebutted.

To this end, Capozzi argued that “consumers are not used to making a comparison between foods of the same category, but their attention is mainly captured by the absolute score.”

The Nutrinform Battery labeling idea, Piretta argued, considers proportionality, with no demonization of the food contents, including saturated fat, sugar or salt.

“With Nutrinform, those are balanced in servings, that means that if you eat your serving of Parmigiano cheese the Battery will show you how much that portion counts in your overall daily intake,” Piretta said. “Nutrinform allows consumers to identify the category of each nutrient and how much it fills up the battery.”

“It is misleading to believe that to combat the obesity epidemic, for instance, we should remove fat or sugars,” Piretta concluded. “We need to focus on education and not on simplification. We cannot hope to win over obesity misleading people, we need the exact opposite.”

Which labeling systems do you prefer?