7.6K reads

7.6K readsWorld

Monte Testaccio: Remnants of an Ancient Trade

Olive oil was a staple in the diet of ancient civilizations, with evidence of a thriving olive oil trade found in Monte Testaccio in Rome, which is a man-made mound made up of millions of smashed olive oil amphorae. The site near the Tiber River was likely chosen for the disposal of used amphorae due to the rancid odour left by the oil, with ongoing research by the University of Barcelona revealing the origin of the vessels and the extent of the trading network supplying olive oil to ancient Rome.

It is well known that the love for olive oil does not simply stem from modern Mediterranean cuisine but was a staple in the diet of the ancients too. Olive groves have lined the villas and farms across the countryside of Greece, Spain and Italy for centuries as they still do today.

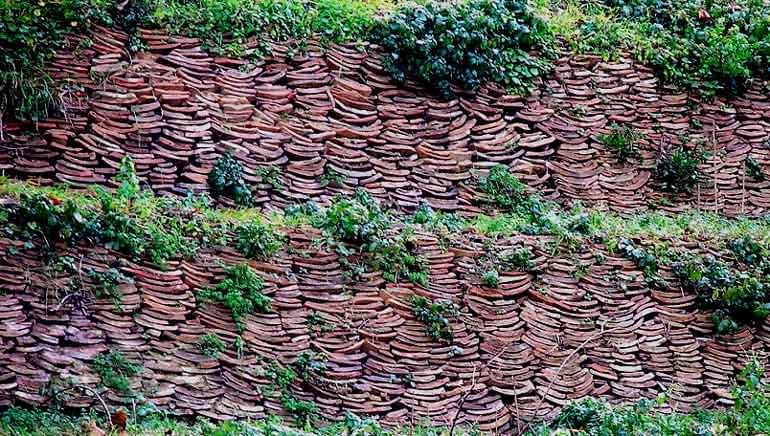

One of the most vivid reminders of the thriving olive oil trade in antiquity is Monte Testaccio in Rome. At first sight, it may simply look like a hill, much like the other seven in Rome that encircle the city. But when you pass through the gates on Via Zabaglia, it soon becomes clear that this is no ordinary mound; it is entirely man-made from the remnants of an estimated 53 million smashed olive oil amphorae.

So why are there so many amphorae sherds in one place? Firstly, the site of the mound on the east bank of the Tiber is located near the Horrea Galbae – a huge complex of state controlled warehouses for the public grain supply as well as wine, food and building materials. As ships came from abroad bearing the olive oil supplies, the transport amphorae were decanted into smaller containers and the used vessels discarded nearby.

There’s a reason for this: Due to the clay utilized to make the amphorae not being lined with a glaze, after transportation of olive oil, the amphorae could not be re-used because the oil created a rancid odour within the fabric of the clay.

The sherds of ancient amphorae that make up Monte Testaccio

Walking up Rampa Heinrich Dressel, named after a late German scholar who studied amphorae extensively, it is amazing to be stepping on so many pieces of evidence from an ancient civilization. From the top of the 36-meter (118-foot) high hill, there is also a great view of the Rome skyline.

The University of Barcelona is currently investigating the hill, looking for amphorae stamps or tituli piniti which could indicate the precise origin of some of the vessels and the contents within them. The type of clay used to make the amphorae can also give an indication of their origin. Most of the vessels in this mound date from the second and third centuries AD from Baetica (Andalusia in Spain) and North Africa.

This indicates an active trading and transportation network through colonies of the Roman Empire and a large demand for olive oil in the capital — over 6 billion liters of oil would have been carried in these vessels to cater to the culinary needs of this busy city of over a million people.