Tunisia: Land of the Olive Tree

An Olive Oil Times reporter traveled to Tunisia to better understand this nation’s olive oil and learn about efforts to increase exports, which was the focus of the second edition of the Olive Festival of Sfax.

Photos by Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil Times

Photos by Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil Times 22.1K reads

22.1K readsThe article explores Tunisia’s deep connection to olive oil, a treasure that is central to the nation’s history, culture, and economy. Tunisia is one of the world’s largest producers of olive oil, with a rich history dating back to Roman times and a tradition of family involvement in olive cultivation. The significance of olive oil in Tunisian life is highlighted by a taxi driver’s belief that it can cure 99 ailments, but not death.

In the heart of the labyrinthine Kasbah of this bustling North African port city, there’s a revered mosque called Al-Zaytuna. It’s a place of historical weight and famed as the Great Mosque because so many Islamic philosophers, jurists and poets walked, prayed and learned here.

In our Bible, the Koran, it says olive oil will cure 99 things. But it does not say it will cure all 100. Why? Because olive oil cannot cure death. It cannot bring you back to life

Most telling, in Arabic, zaytuna means olive tree — and so, just as this famous mosque called “the olive tree” lies at the core of Tunisia’s history and life, the olive tree is rooted at the center of this nation of 11 million people.

Olives — and in particular olive oil — are Tunisia’s unique and, oddly, unknown treasure.

An Olive Oil Times reporter went to Tunisia to better understand this nation’s olive oil and learn about its efforts to increase its exports, which was the focus of the second edition of the Olive Festival of Sfax, an international event that took place at the end of January.

“We use it for cooking, for salads, for everything,” said Adel Ben Ali, a friendly and warm-smiled vendor in the Marché Central, a large covered market in Tunis where fresh produce of every color and taste is sold with great gusto and flare.

See Also:Gold for Tunisia Heralds Start of New Beginning

Tunisia is a land of olives, a place where the olive tree over the millennia has become infused with the nation’s culture, economy, cuisine, habits, rhythms, seasons. Some Tunisians even anoint newborns with olive oil.

Indeed, Tunisia is one of the world’s biggest producers of olive oil — a little-known fact to most people who aren’t olive oil cognoscenti. Across its landscape, olives are found. There are about 1.8 million hectares of olive groves with 82 million trees — or about 30 percent of this North African country’s cultivated land.

Photos by Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil Times

In the common imagination, the making of olive oil can appear almost exclusive to Italy and Greece, where olive oil is poured onto all sorts of food with healthy abandon. When people think of a Mediterranean diet, and the healthy olive at the center of meals, they think, with good reason, of Rome and ancient Athens.

And yet, in these notions of olive oil, the story of Tunisia and its ancient cultivation of the olive tree is left out of the picture. Indeed, Tunisia’s history of olive cultivation is ancient.

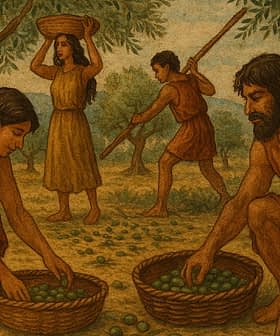

In the entrance of a multistory building in a business district of Tunis housing the Office National de l’Huile, a state agency dedicated to olive oil, there’s a wall-sized painting of the olive harvest. It is a vivid portrayal of farming families in an olive orchard at the start of a new harvest.

“This is a traditional picking of olives,” said Chokri Bayoudh, the agency’s chairman, during an interview with Olive Oil Times. “It is a painting by someone who loved olive oil.”

It’s a complete scene: A woman in the foreground uses a thresher to separate out olive leaves, twigs and dirt. Nearby, tea is brewing on a smoldering fire next to a man wearing a traditional Tunisian hat, the deep red beret-like chechia, while his wife, her head covered in simple headscarf, sorts through newly picked olives.

There is much more going on too.

People clamber on ladders in the backdrop, picking olives, and a boy — perhaps the painter himself? — appears enchanted at the center of the work of art. This boy is not lifting a finger, content as he is to muse on the moment of the great harvesting, the continuation of a tradition.

Bayoudh stood and admired the painting.

“And now, you can see this in every region of Tunisia,” he said, speaking English. “We work like this, with children, with women, with wives, with all of the family.”

A man carrying a tray of clinking tea glasses walked by as he spoke. Outside, Tunis’ traffic honked and pushed forward. Bustling. A phone rang, urgently.

The olive tree flourishes here – despite Tunisia’s aridity and desert soils.

Establishing an exact history of how and when the olive tree arrived in Tunisia is nearly impossible to determine, according to Tiziano Caruso, an olive tree expert at the University of Palermo in Sicily.

“It is very difficult to say when the olive arrived.”

Nonetheless, the Phoenicians certainly played a major role in cultivating the olive tree and it was then spread by Carthaginians, who planted olives where and when they could, especially in times of peace, according to Tunisian authorities.

On the peninsula of Cap Bon, the oldest known olive tree in Tunisia can be found. It dates back to around 2,500 years ago. The big ancient tree was planted during the Carthaginian reign and olive lovers to this day make pilgrimages to eat its fruit.

Then came the Romans.

Under Roman rule, olive cultivation was expanded along with irrigation and methods of olive oil extraction. The olive responded: Tunisia’s aridity and sun were just right for olive cultivation.

For centuries, the Romans watched it flourish and grew wealthy, building stunning structures in Tunisia: great palaces, villas, the massive amphitheater in El Jem, cities, aqueducts.

Olive cultivation largely ceased after Arab conquests during the Middle Ages.

“The olive orchards disappeared progressively until the French colonization in 1881,” said Raouf Ellouze, a Tunisian olive oil maker and leader of Synagri, a farmers’ syndicate. He said Arab nomads cut down olive plantations to make way for grazing land.

Olive cultivation flourished anew under French rule, especially after a series of discoveries by Paul Bourde, a colonial administrator and journalist who was also a classmate of French poet Arthur Rimbaud.

In 1889, Bourde, as the protectorate’s agriculture director, traveled through Tunisia and made a series of remarkable findings. Big stones in the semi-arid steppes in central Tunisia, he argued, were left over from ancient Roman olive mills. Indeed, he argued that olive cultivation was possible in the vast empty spaces of Tunisia.

Today, Tunisia is one of the world’s top producers of oil. Olive groves extend for miles and miles where a century ago semi-arid steppe reigned. Tunisians are proud of their olive oil.

“Our olive oil is the best in the world,” a Tunisian taxi driver said as he maneuvered with ease through the hectic Tunis traffic, a flow of cars pushing against one another.

The taxi driver kept talking. He was in his element: He was talking about olive oil. He owns a small piece of land on the city’s outskirts with three olive trees and his family picks its fruit together, a scene reminiscent of the painting at the Office National de l’Huile.

“In our Bible, the Koran, it says olive oil will cure 99 things. But it does not say it will cure all 100. Why?” he pondered, fudging a bit his citation.

The streets flew by, as did cars, buses, motor scooters, roundabouts, bumper to bumper traffic. A woman, her head swathed in a traditional Muslim scarf, drove past. A girl unbuckled in another car stood in the back seat, watching the traffic.

“Because olive oil cannot cure death,” he said with a grin. “It cannot bring you back to life.”