Invasive Sheep Devastate Olive Groves in Eastern Spain

Over the past 50 years, invasive species like the Barbary sheep have rapidly increased in both population and range, leading to more frequent interactions with agriculture.

Barbary sheep populations have multipilied in southern Spain over the past 50 years.

Barbary sheep populations have multipilied in southern Spain over the past 50 years. L’ALCOIÀ, Spain – The Valencian Community’s Unió Llauradora i Ramadera (Farming and Livestock Union) has again drawn attention to the agricultural damage caused by wildlife in the Alicante Mountains, particularly emphasizing the effects of invasive species such as the Barbary sheep.

In a study published in August, the union estimated that damage from ungulates causes direct losses for farmers in the region of €10 million annually, approximately €4.7 million or 47 percent, of which was incurred by olive groves.

The regions of Marina Alta, Marina Baixa, El Comtat, L’Alcoià, L’Alacantí and Alto y Medio Vinalopó were found to be most severely affected.

With an integrated and sustainable approach, it is possible to protect the interests of farmers while conserving the natural wealth that defines this beautiful region.

One of the animals highlighted in the study is the Barbary sheep, a wild bovid endemic to regions of the Sahara. Although increasingly rare in its native range, it has proliferated in many areas to which it has been introduced.

In Spain, this first occurred in the Sierra Espuña Regional Park, where the sheep was introduced as a game species in 1970. Since then, it has spread to at least eight different provinces. The population in Alicante alone is now estimated to comprise approximately 2,500 individuals.

Invasive species originating in North Africa are believed to be proliferating more rapidly than in previous decades because of the increasing rate of desertification that is transforming the Spanish landscape into one more akin to their native habitat. This is particularly true of the Alicante Mountains.

See Also:How the Iberian Ant Can Help Control Pests in Olive GrovesBecause of its adaptations to mountainous, arid terrain and its ability to feed on a vast array of woody plant species, the Barbary sheep can cause considerable damage to traditional mountainside olive groves. In addition, it can perform a standing jump of more than two meters, making standard fencing ineffective.

The union used the case of Miguel Ángel García as an example of the problems facing farmers because of these species. An olive farmer and oil producer in L’Alcoià, his plot closest to the mountains has suffered extensive and increasing damage over recent years, with the 2023 harvest totaling only 300 kilograms: 1,000 kilograms less than the previous year.

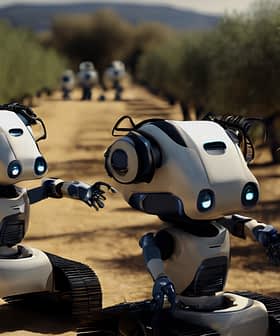

Barbary sheep are damaging the olive trees in the Alicante Mountains. (Photo: Simon Roots)

Speaking to the Olive Oil Times, L’Alcoià locals expressed a range of opinions on the presence of the exotic species, none of them positive. While all were concerned about the animals’ effects on the local economy and traditions, many believed their environmental impact was of even greater concern.

The area is renowned for its natural beauty, and its mountains and ravines provide an important refuge for many species found only on the Iberian peninsula. In addition to increasing competition for food and habitat, invasive exotic species are vectors of various diseases that can spread to native wildlife and livestock.

Another recognized danger the animals pose is their ability to jump roadside barriers, leading to increased traffic accidents in the regions where their numbers have soared.

Such a comprehensive range of problems means that calls to control the populations of these species have broad support. However, the situation is complicated by frequently changing and even contradictory legislation, as successive governments bring opposing ideologies and priorities to bear.

The Barbary sheep, for example, was included in the Spanish catalog of invasive alien species in 2013, meaning that the national government’s official policy was to eradicate the species entirely from the country.

Hunting groups, however, obtained an exception for the region of Murcia, the point of origin for the species in Spain. In 2016, however, a Supreme Court judgment removed this and other exceptions and reiterated that all invasive alien species must be eradicated.

However, in 2018, the 2007 Natural Heritage and Biodiversity legislation was reformed, effectively reverseing the 2016 judgment.

Despite efforts to hunt the invasive sheep, prohibitions on such activities in protected areas has hindered the effort. (Photo: Simon Roots)

With this reform, alien species that were already invasive before 2007 are no longer subject to eradication. Instead, they are subject to control through hunting and fishing. Even further complicating the situation is that hunting is illegal in protected environment areas, and hunting legislation varies between autonomous communities.

However, many residents believe an effective balance can be found within the current framework.

“The balance between the conservation of game fauna and the protection of agriculture is a complex but manageable challenge,” García said. “The Alicante Mountains, with their rich biodiversity and important agricultural sector, can serve as a model for other regions facing similar problems.”

“With an integrated and sustainable approach, it is possible to protect the interests of farmers while conserving the natural wealth that defines this beautiful region,” he added. “It is therefore crucial to implement sustainable management strategies that balance the conservation of game fauna with the protection of agriculture.”

Another contentious issue is compensation. While wildlife management is the Department of the Environment’s responsibility, the Department of Agriculture is responsible for compensating farmers for losses incurred by wildlife damage and providing aid for preventative measures.

In June of this year, however, the Department of Agriculture announced that it would provide funds only for preventative measures in the Valencian Community and not for compensation as previously announced. Furthermore, the funds appropriated for these measures amounted to €250,000, a figure in stark contrast to the €6.3 million in neighboring Catalonia’s budget.

According to the union’s data, total losses from wildlife damage in rural Valencia in 2023 amounted to over €45 million.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food has previously stated that current measures are not sufficient to curb the expansion of various species or the frequency and magnitude of their impacts on human activities and the natural environment. It has spoken specifically of wild boar, roe deer, barbary sheep, ibex, mouflon and rabbit, which are increasing in population and range.