Revolution in Extremadura’s Olive Sector Increases Its Economic Importance

Extremadura’s sector is undergoing an important transformation with the expansion of intensive olive crops.

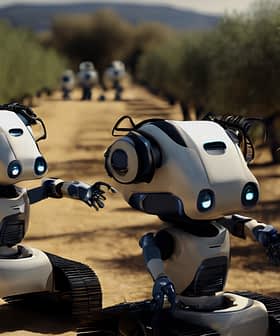

Intensive olive tree farming, Badajoz, Spain

Intensive olive tree farming, Badajoz, SpainNational and global distinctions to the quality of its olive oils, changes in their packaging and image, new approaches to olive cultivation and processing, and a greater product presence in international markets are some ingredients of the transformation of Extremadura’s olive sector, a change that is helping olive oil become a more relevant product in the economy of this Spanish community.

The metamorphosis derives from a continued growth resulting from intensive olive grove farming. This has helped expand the cultivated surface to the point olives are now Extremadura’s largest crop.

Intensive and super intensive olive cultivation offers advantages that have contributed to its proliferation in Extremadura in the last few years. Intensive and super intensive methods facilitate mechanization, easing management and saving costs. Their irrigation grants stability to the crops. The reduced harvesting costs lead to a more profitable effort amid a growing global demand and reduced production in some other olive growing areas.

Extremadura’s olive sector’s revolution is led by Badajoz, Spain’s top olive oil producer outside Andalusia. Badajoz represents 88.6 percent of Extremadura’s olive production, 3.5 percent of Spain’s production and 1.7 percent of the world’s production.

Between 2006 and 2017 Badajoz’s olive grove surface grew by almost 25 percent. Although traditional groves still represent around 80 percent of the region’s total surface, intensive, irrigated groves are growing at a faster pace of 67.5 percent versus 9 percent of traditional plantations.

Badajoz and Cáceres are the main olive oil-producing provinces in Extremadura, which in the 2017/18 campaign harvested a total of 73,000 tons of olives, a figure that is expected to reach 100,000 soon. This increase has had an impact on olive mills, which are adapting their facilities to handle a larger production with greater quality and also making a bet on olive tourism. Private label olive oil brands also grew significantly in the region.

Extremadura has several authorized olive varieties for olive oil and table olives including Manzanilla de Sevilla, Cornicabra, Picual, Morisca, Cornezuelo and Verdial de Badajoz.

Manzanilla Cacereña is the region’s olive star and was responsible for helping promote Extremaduran brands internationally. Some projects are revitalizing rare varieties like Azulejo or Pico Limón, grown on centenary trees.

Gata-Hurdes and Aceite Monterrubio are the community’s two DOPs for olive oil and are promoted by Alimentos de Extremadura, the community’s promotional body for its geographic designations. Both produce outstanding oils with fruity aromas.

Gata-Hurdes protects EVOO obtained exclusively from olives of the Manzanilla Cacereña variety harvested by hand.

Monterrubio’s olive groves are younger but produce a very high-quality olive oil from Cornezuelo, Picual or Jabata varieties. Only EVOOs with an acidity of less than 1 percent are certified.

Quality improvement of olive oils has been a key complement to intensive cultivation methods in the transformation of Extremadura’s olive oil sector. One major difference has been that olives are now harvested earlier with the objective of obtaining more fruity and aromatic oils with longer shelf lives, even if this might significantly lower yields.

This quality has been recognized locally, where more oils are qualified as extra virgin, and internationally at competitions including the NYIOOC World Olive Oil Competition. Some companies are already exporting oils to international markets as Italy or the United States.

Innovation is also at the industry’s forefront. An example is Ecolibor, a company in Cáceres that produced an olive oil with unusually high phenolic levels, which is attributed mainly to Extremadura’s terroir.

It is expected that approximately 20,000 new olive grove hectares will be planted in the next few years and it appears intensive and super intensive plantings will lead the future path of the olive oil sector in Extremadura, offering competitive price options for more professional crops, while representing another challenge to traditional olive groves with higher production costs.