Sicily's Monumental Olive Trees Provide Window Into Island’s History

Sicily’s oldest olive trees have stories to tell. From farmers overcoming adversity to the island becoming a trade hub, olive oil production played an essential part.

Sicily’s soil and climate are ideal for olive cultivation, and wild olive trees have long grown on the island.

Now researchers are learning more about the history of olive oil on Sicily from archaeological evidence – and from the ancient olive trees still growing throughout the countryside.

Believed to be the island’s oldest olive tree, the Olivo di Innari is also its largest. At 19.6 meters in circumference, this 2,081-year-old tree was planted when Sicily was a Roman province.

See Also:Producers on Sicily and Sardinia Prevail in World CompetitionSicily’s smaller farmers labored under onerous taxes and duties from the Romans and their local governors. At the time, Sicily was known primarily for its wheat and wool exports.

Some speculate that a hard-pressed local farmer planted Innari in hopes of cashing in on the Roman market’s rapacious demand for olive oil. Today Pettineo, the town where Innari still grows, remains an agricultural center and is mainly well known for its local olive oil.

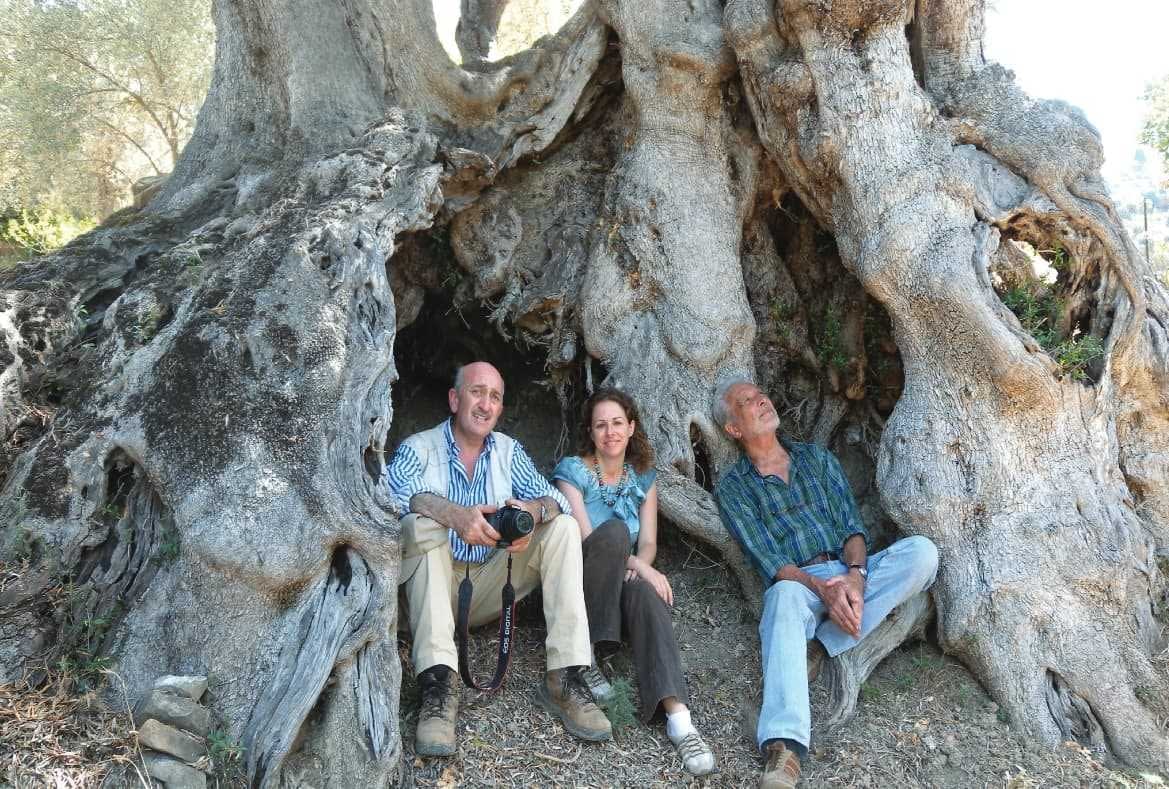

Olivo di Innari (Rosario Schicchi / Francesco M. Raimondo)

One millennium after Olivo di Innari was planted, around the year 1000 C.E., the historic village of Calacte (from the Greek for “Fair Isle”) was razed in the Arab-Byzantine wars.

However, the fighters spared an enormous centuries-old olive tree. Today, the 12.9‑meter round, 1,369-year-old Olivo de Predica still stands in the rebuilt village, which the 11th-century survivors named Caroniam, or “new house.”

While Sicily’s oldest olive trees are around 1,000 to 2,000 years old, soil cores near Lago di Pergusa in central Sicily show a spike in olive pollen between 3,000 and 3,200 years ago.

This coincides with the arrival of the Sicels and Sicanians who gave the island its name. Lake Pergusa is outside the wild olive tree’s normal coastal distribution, so it appears the newcomers brought olive cuttings with them.

The Olivo di Nicoletta, a few miles from Lake Pergusa, is smaller than the Predica tree at 7.9 meters round. It is also a few centuries younger, at an estimated 828 years old.

See Also:Pottery Shards in Croatia Reveal Roman Olive Oil and Military HistoryWhen Nicoletta was planted, the king of Sicily and Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI was seizing power over the island and its lucrative olive oil and fabric industries. Along with providing fuel for lamps, lampante olive oil was also used to lubricate the looms used to manufacture the fabric.

Meanwhile, Avola, a small town in Sicily’s Siracusa province, is home to a 1,684-year-old olive tree with a massive 15.5‑meter circumference, the Olivo di Contrada La Gebbia.

At the time of La Gebbia’s planting, fourth century Sicily’s economy was booming, in large part, due to the growing olive oil trade between Sicily and the rest of the Empire.

Old as all these trees may be, archaeologists have found even earlier evidence of Sicilian olive oil production.

In Castelluccio, a rural town 32 kilometers from Avola, recent research has produced evidence that sets the earliest date for systematic oil production in Italy back 700 years.

In 2018, history professor Davide Tanasi of the University of South Florida reported a chemical analysis of fragments from a 4,000-year-old storage vase found in an early Bronze Age village outside Castelluccio. The fragments showed traces of oleic and linoleic acids, signatures of olive oil.

Before this find, the earliest Italian olive oil signatures came from 3,300-year-old pottery fragments found on the southern mainland.

The Castelluccio pot shows that the Sicels and Sicanians did not bring olive oil production to Sicily but instead took over an industry that had been ongoing for centuries.