By Julie Butler

Olive Oil Times Contributor | Reporting from Barcelona

February 4th was the 2011 closing date for entries for one of the world’s most influential olive oil guides, published annually by Germany’s top gastronomical magazine, Der Feinschmecker (literally “The Gourmet”). This year, 800 oils were entered for inclusion in the Olio Awards guide, which will come out this June. Kersten Wetenkamp has been the magazine’s food and wine editor for a decade and since 2003 has overseen the guide. From his native Hamburg, he tells us about the arduous selection process and trends he sees in the olive oil sector.

How did you get started in gourmet writing?

How did you get started in gourmet writing?

I had always wanted to write about culture (literature, movies) but good food and wine has always been important in my family. My mother gave cooking-lessons in a school, so there was a good level of cuisine at home. During my journalism studies in Hamburg, I took the opportunity to do two-months’ work experience at Der Feinschmecker and this turned out to be very enjoyable and fun (we had wine tastings every day!). I started my editor’s job in 2000 after four year’s editing an economics and IT magazine.

What inspired the olive oil guide?

We started it in 2003 because there was nothing like it in the market. It was a pioneering work. Who knew about olive oil at that time? There were very few experts in Germany so we invited them from Italy, Greece and Spain to come to Hamburg and taste olive oils. We had a database with several hundred food retailers and we asked everybody to send us olive oil. In the end, we were astonished to see thousands of olive oil bottles in our office!

Please tell us about the selection process and the role the guide plays.

Please tell us about the selection process and the role the guide plays.

The process is very simple. Anyone who wants to can enter but they must pay 29 euros per oil, due to the high cost of the tasting. We handle about 900 olive oils from nearly every producer country. Herb-infused oils are not permitted, and from the beginning the producer’s name has had to appear on the bottle or we won’t accept the oil. Biological and DOP olive oils are the exceptions to this rule. I believe our sensory analysis is one of the most rigorous in the world. In the end, only 200 – 250 will make it to publication. Our guide is primarily important for the German market, where it plays a key role for producers who depend more or less on the German retailers. Many Greek and Italian producers also pay great attention to our guide.

What trends have you noticed?

The greatest change I have seen is with the image of Spanish oils. When we began, there was a real prejudice about Spanish olive oils — that they were for quantity but not quality. Indeed, around 2003, Spanish oils were rarely seen in German supermarkets, except for “anonymous” industrial products labeled “Made in Spain” that were probably a mix of Greek, Spanish and African oils.

I wrote an article in WirtschaftsWoche, a German business magazine, about the lack of quality-consciousness in Spain, compared with the consistently high quality of New World oils from countries like Australia and the USA. This made the Spanish Chamber of Commerce really angry. But since then, things have changed radically and Spanish olive oil producers are now among the very best in our competition. It seems that the producers see their niche, their corner in the market in Germany. In what is quite a revolution, they now put the producer’s name on the label.

Secondly, there is a trend towards traceability, as we have seen in Crete, where producers give a certain transparency to their product, to let customers trace the source of the olives through to the bottling date. Slowly, this will be printed on more and more labels thanks to demand from the media and customers.

Thirdly, ecological production is still demanded in Germany and there will be more and more oils with the eco-label. Does this make sense? I am not sure, but that’s the market. Finally, in Italy we are seeing more and more producers removing the stones before pressing their olives. These special new oils, denocciolato or snocciolato, are sometimes good (well-balanced) and sometimes not (unbalanced). Consequently, these oils tend to have a more bitter, stronger taste and a higher level of polyphenols. In Germany, olive oil consumption is growing rapidly and the trend is towards increasing interest in quality.

You are editing a book due out in 2011, what is it about?

You are editing a book due out in 2011, what is it about?

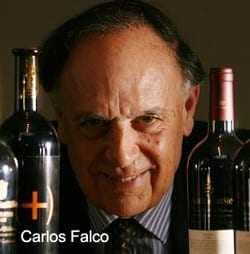

It’s a manuscript by Toledo’s Carlos Falco about his experience with the most modern olive mill in the world, including his collaboration with Tuscany’s Marco Mugelli, one of the globe’s leading olive oil experts. The resulting oil, Marques de Griñon, is one of the best. The book is being released by Der Feinschmecker’s publisher, Hoffmann and Campe, and in both German and English. It’s about the history and benefits of olive oil production and consumption. But even more interesting, it will include the personal view of this great wine and olive oil pioneer. It’s aimed at a general readership in Germany and wider Europe.

How do you use olive oil?

I use olive oil every day, mostly in the evening with dishes, on bread, bruschetta, salads and fish. I am conscious of trying to eat healthily and try to follow a Cretan diet, with a lot of seafood and fruits and vegetables. On weekends, I always use a lot of olive oil for frying.