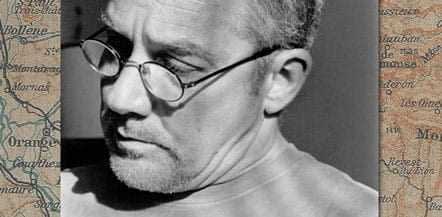

The name Steve Jenkins is synonymous with Guru, Expert, and Savant in the world of Mediterranean foodstuffs. In 1976, Jenkins was the first American cheesemonger inducted into France’s ancient and elite Guilde des Fromagers (he has since been elevated to Prud’homme, the guild’s highest status). Author of Cheese Primer and The Food Life, Jenkins was recently named one of the 25 most important people in the history of the American specialty foods industry by Gourmet Retailer.

He has introduced countless cheeses and other foodstuffs to New Yorkers (and subsequently the rest of the United States) by pioneering the importation of traditional and artisanal foods from over a hundred European companies to New York City’s wildly successful Fairway Markets. A regular guest on the award-winning NPR program, The Splendid Table, Jenkins knows his (food) stuff, and he wants you to know he’s not fooling around.

So how does one become an “Idiot Savant” as Jenkins so eloquently puts it? Years upon years upon years of studying, traveling, and finding joy in discovering new sights, sounds, smells, and tastes all over the world — that’s how. Jenkins will be the first to tell you, “It’s out of a passion for being out there in that area, smelling those smells, eating in those joints, staying in those little hotels and driving, driving, driving, and talking to people.”

Raised in the suburban Midwest, Jenkins remembers the meals of his childhood with a wistful appetite — as though he’s not yet had his fill. “My mother and my grandmother were terrific cooks, but they were merely regional cooks — Missouri cooking via Kentucky. They were not at all versed in the Mediterranean style or with any kind of European food whatsoever. So I was without any sophistication other than a love for good ingredients that were prepared traditionally.”

“My grandmother and grandfather had a garden that was just mind-blowing. My joy probably stems from their garden-fresh lettuce salad wilted with vinegar and bacon grease, tomatoes, apples, carrots, all those wonderful things. There was no winemaking, no olive oil, we didn’t use fresh herbs in the Midwest, no seafood — we never had any seafood! We really had very little to work with other than the things we loved like roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, chili and fried chicken. Our country grew up so fast we had no time to create any tradition or any kind of heritage for food other than about a hundred years ago; butchering hogs on a farm, chopping the heads off of chickens, and a great garden near the kitchen.”

From fried chicken to French cheeses? Early on Jenkins decided that he wanted to be unassailable when it came to being approached in a food shop counter situation by anyone from any walk of life when asked about certain foodstuff, ingredient, procedure, recipe, domain — anything. “I wanted to know everything there was to know about all of the foods.”

“Every night as I’d lay in bed I’d be reading about the places, the people, and the things that they loved to put in their mouths. I did it all dealing with maps — I found that I had a great love and respect for maps, and I got such joy out of dreaming of jumping up in the air and coming down on this place on the map. I could only imagine what was going on in Savoie 400 years ago, I could only imagine what those woods looked like, how close Piemonte was and how it was a part of Savoie then.”

“It was all born out of studying maps and having an appreciation and regard for the fact that all of this food has nothing to do with country — it has to do with the specific regions and subregions it came from. Year after year, I’d get in a car with my maps and drive down all the little roads seeking out villages that gave their names to certain foodstuffs. You find that over 10 years you build up a nice body of knowledge, after 20 years you’re a bloody expert, after 30 years you’re a savant, and after 35 years it’s been such a joy, such a great way to fall asleep at night.”

Jenkins took his first trip to Europe in 1978, when he was 27 years old and working for Dean & DeLuca. Since then every single season that passes, he craves to be in Europe. “I’m lucky to be there two seasons of the year,” he says. “I always go in October, harvest time, and then I try to get there in the winter, spring or summer. I love going places in the dead of winter; you’re just invisible, yet at the same time you get more attention because no one really travels in the winter — if you’re there you’re serious, they take you seriously.”

In early 1979 there was very little quality olive oil available to NYC retailers. Jenkins evokes memories of big brand ‘pure’ grade olive oils found in Italian grocery stores, like Amastra, “Bright green for no good reason, and purportedly from Sicily.” Regular supermarkets sold Goya, Bertolli and Berio, and fancy shops like D&D and Balducci’s had access to phony brands of EVOO but “It wasn’t EVOO, and I could prove it!” Just three olive oils — Hilaire Fabre, Plagniol and Louis de Regis — all purportedly from France, but undoubtedly from Spain bottled in France.

“At this point, I had read my Elizabeth David, and my MFK Fisher, my Roy Andries Degroot and my Richard Olney, and I knew there was a lot of serious olive oil out there. So I made it my business to get my hands on it. I started with the Tuscan Badia a Coltibuono and the Provencale L’Olivier (which I much later learned was also cheap Andalusian oil bottled in France.)”

By 1980, Jenkins had found his home in Fairway Markets, and was well along pioneering literally every great French cheese in France (and just starting in on Italy via Peck’s La Casa del Formaggio owned by the Stoppani brothers in Milan) when he was inspired to do the same with olive oil. “The one experience that galvanized me as to the notion of selling the best olive oil came after I fell into A l’Olivier, an olive oil shop on the Rue de Rivoli in Paris: Huge terracotta amphorae, fabulous chevron-shaped labels, crystalline bottles of all sizes, and dark green masculine tins all filled with extra virgin olive oil. Some of it may actually have come from olives grown in Provence! I realized no one in New York had any appreciation for olive oil, exactly as they had no knowledge, regard or desire for serious cheese.”

Jenkins and his mentor and founder of Fairway Markets, David Sneddon, began growing and harvesting their own olives in the Umbrian region of Italy — they’d been converted; olive oil coursed through their veins. Sneddon recalls picking and pressing the olives in November while the scent of burning grass lingered in the air and the cows descended from nearby mountains towards warmer microclimates for the winter. In April, when the two opened their olive oil for the first time, rubbed it on their hands, and held it up to their faces, they were enveloped by the scents of that cool November day — smoky earthy tones, reminding them of the back-breaking work it took to obtain those bottles of gold. Proving that it really is a labor of love.

Sometime after 9/11, Jenkins and one of his Fairway partners, Brian Riesenburger, got really involved in olive oil. “We just did what came naturally; we did the same thing with olive oil and vinegar that we had done with cheese — we set the standard for the industry, and we set the bar very high because we know so intimately the geography of the Mediterranean Basin. We’re idiot savants. We bring our hobby into our stores, just like people do with stamps or bugs or butterflies or birds — for us it’s olive oil and vinegars, cheeses and all the Mediterranean ingredients.”

Jenkins stocks around 100 EVOOs at Fairway Markets, and travels to his groves in all seasons several times a year — some of them, of course, not all because they deal with too many. So he travels to new groves, and to those groves that are longest-standing and most important, like two in Extremadura and Andalusia, several in Western Sicily, in Catalonia, and many elsewhere, including Umbria, Sardinia, Tuscany, Molise, Liguria, Lazio, Puglia, and certainly all over the South of France, from Languedoc and the Camargue to Corsica and Provence.

“It’s a Mediterranean Basin phenomenon,” says Jenkins, “yes there’s olive oil in New Zealand, in Australia, in Lebanon, Algeria, and some in Egypt and Israel — and we’ll address it — but unless it tastes so good to us that we can’t resist it, we don’t include it. At Fairway Markets, we’re not inclusive of oils just because they exist, we are only inclusive of olive oil that passes what we think is a rigorous test: our own palette. That’s as subjective as can be, but it’s true. If we don’t love it, it ain’t gonna make the cut. There are no oils from Syria, Turkey, or even my beloved Tunisia that have met the standard, which is, ‘Do we love it?’

Jenkins imports 24 French oils, direct and exclusively from the producer, as well as a dozen very specific oils from Spanish farmers (“My Alcubilla Luque oils from near Baena are the only EVOOs available in the US that are still pressed the old way, from fanatically certified organic olives that yield a flor de aceite that is, a ‘pre-extra-virgin’ oil.”) and around ten very specific oils from locally famous Italian families in Liguria, Tuscany, Umbria, Lazio and Sicily. “However, my most satisfying accomplishment is the 14 (not 12, not 15) very specific oils from Spain, France, Italy, Australia, California and Mexico (yes, Mexico!) that I induced the farmers to sell to me in barrels, unfiltered,” says Jenkins.

“I cut out more than the middle man when I buy by the barrel — I’m cutting out the broker, the importer, and the distributor. That oil came not just from a farmer, it came from the mill, which pressed the olives and sold the oil to a broker who sold it to the American importer who’s been nosing around looking for the cheapest oil he can get, who brings it into NY or wherever and sells it to the distributor who sells it to the retailer. There’s nobody between me in the store talking to people about the olive oil they just tasted, and the farmer who grew the olives.”

“Not to mention, I bottle these 14 oils myself — that’s half as expensive right there. The fancy European bottle and label easily adds on 5 to 7 euros — that’s how much the oil should cost! Then I’m able to market each oil with a label I made myself that features everything I want my customer to know about the oil — where exactly it came from, when exactly it was harvested, how many hours elapsed between picking and mulching, the centrifuging, and how long it was allowed to decant; the variety of olive or olives, the things I smell in them, the things I taste in them, their textures, attacks, interims and finishes; and finally my favorite uses for each of them. I only wish the labels were bigger so I could put maps on the bottles.”

At Fairway Markets, you’ll find maps, posters, and photos of the olive groves splashed all over the store — “It’s olive oil porno everywhere you go!” Huge tasting cupboards hold a container filled with 24 to 36 different EVOOs in all of the stores. “People get excited about the particular area that these oils come from, and they make it their business to go there,” says Jenkins. “They’ll go to Barcelona and rent a car and drive down to the Ebro River Delta and see the Cocons oil from Catalonia that’s one of my absolute favorites, and they’ll see those flat stones for which the oil was named. They’ll go there because of what’s on the label of that bottle that acquaints you with exactly where it came from. It’s a geographic lesson — what’s cooler than that?”

Over the years, Jenkins has seen very little change within the olive oil industry, saying that he’s found that more and more people think they know something about olive oil, “But in truth, they are filled with lies. If you’re interested in olive oil and you go on the internet and try to learn more about it, there’s more and more misinformation, and nonsense, and absolute factual bologna than had there not been any internet at all. If customers don’t travel, at least go to one grove in the entire Mediterranean Basin, they’re not going to learn about olive oil.”

“My customers in the Tri-State area of NY are as sophisticated as any in the world, they’re well-traveled, yet they still had no grasp or regard for the region of olive oil — they knew not a wit. I had to teach them the same way I did about cheese — it took years to bring their appreciation up to where I can now have 7 cheese counters that are far better than anything in the world in terms of its breadth, depth, and quality. It’s the same thing with olive oil, it’s taking a long time to get people to pay some respect to it rather than just spending $40.00 on a half-liter with a beautiful label and thinking, ‘I must be pretty smart about olive oil.’ While in reality, the oil was 2 years old, it’s already stale, you paid 4 times what the oil was worth and you know nothing about where it came from.”

“My mission, on the other hand, is to make sure the customer knows exactly where their olive oil came from, pays as little as humanly possible, and the oil tastes better than anything he or she ever, ever put in their mouth — the finest ingredient they could possibly have anywhere in the world. That’s my mission. That’s what I’ve been building up over the past decade — a rather sizable cadre of people who have really strong likes and dislikes for specific olive oils. That’s as good as it gets right there.”

So go to a Fairway Market, taste one or two or twenty olive oils from around the globe. Let the labels and photos transport you to faraway lands, down dusty roads, where the cows are still milked every morning, the eggs are fresh, and a garden overflows onto the kitchen counter. Ask Steve anything — really, anything — about food, and experience for yourself what a lifetime of knowledge and absolute passion for the highest quality ingredients is all about. Take a piece of the Mediterranean Basin home with you, drizzle it over fresh fish and wilted lettuce salad, dip a warm baguette into the depths of its fragrant golden pools, and really think about what you’re smelling and tasting. Does it pass your palette test? Do you love it? Maybe even enough to pull out a map and plan your next adventure? Because that’s what it’s all about — eating is experiencing, and when the eating is this good, it’s transcendental.