Tunisian Women Producers Making a Mark in a Man's World

Women are making their mark on Tunisia's fast-growing olive oil industry, even if it's often behind the scenes.

Zakia Hajabdallah in her olive grove. Photo by Isabel Putinja.

Zakia Hajabdallah in her olive grove. Photo by Isabel Putinja.Women play a significant role in Tunisia’s olive oil industry, both as laborers during harvest season and as managers of family-run businesses. Despite challenges such as unequal inheritance laws and water scarcity, women like Zakia Hajabdallah and the Ben Hamouda sisters are making strides in producing high-quality olive oil and advocating for the industry’s development.

Much like wine-making, the world of olive oil is largely a male-dominated industry. This is also true in Tunisia, where one-third of the land is covered in olive groves and 300,000 people work in olive oil production.

But many of these are women who are making a significant mark on Tunisia’s fast-growing olive oil industry, even if it’s often from somewhere behind the scenes.

Olive producers in Tunisia are getting noticed but there’s more to be done.It’s only together than we can promote the image of Tunisian olive oil.

The biggest contribution of women to an industry worth 2 billion Tunisian dinars ($723.7 million) in exports has been as a source of cheap labor during the harvest season. Ninety percent of harvest workers are rural women who work as seasonal agricultural laborers. They are generally paid a daily wage which is often less than that earned by the male workers doing the same job.

A small part of their daily wage goes to pay for transportation from their villages to the olive groves which is usually organized by their employers, the farm owners. Bundled in multiple layers of clothing against the winter cold, the women harvesters spend their working day plucking the olive fruits from the trees by hand.

At the other end of the social spectrum are highly educated women involved in the everyday management of their families’ olive oil businesses. At the Tunisian Olive Oil Awards organized by the Ministry of Industry this past April, several women climbed the podium to collect awards at a flashy ceremony held at a high-end hotel.

Semia Salma Belkhira, general manager of family-run Medagro, received the second prize for a medium fruity Ruspina olive oil; while Rawia Ben Ammar, sales manager at Domaine Ben Ammar organic farm, took home the first prize for the family’s brand Société Mutuelle de Services Agricoles (SMSA), a farmers’ cooperative bringing together agricultural workers in the town of Fahs and neighboring areas. She also wears the hat of VP of the Union Régionale de l’Agriculture et de la Pêche, a union of agricultural workers; and is active in the Fédération Nationale des Agricultrices which represents women farmers.

Zakia Hajabdallah (Photo by Isabel Putinja)

Hajabdallah wears a headscarf and drives a white Toyota pick up truck. This image is not incongruous in Tunisia, a country where women like to do things on their own terms and where they have long had rights and freedoms their sisters in some other Arab countries don’t.

“Women generally work with their fathers and husbands on family farms,” she said from behind the wheel of her pick-up. She explains that one reason why women own so little land is that the current inheritance law works against them: women can only inherit half of what their brothers do. The current government has proposed to revise this law, which if passed would make Tunisia the first country in the Arab world to grant equal inheritance rights.

The drive from Fahs to her olive farm winds through a landscape of undulating hills punctuated by the looming mountains of the governorate of Zaghouan, some 60 km south-west of the capital Tunis. This is an agricultural region where 80 percent of inhabitants make a living from the land.

Olive groves in the region of Zaghouan. (Photo by Isabel Putinja)

Hajabdallah became an olive farmer when she decided to quit her public sector job as an agronomist to work the land she leased from the government as part of a scheme to rehabilitate agricultural land and provide a boost to local farmers.

Bordered by imposing cactus plants, her plot of land stretches over 40 hectares and is planted mostly with long neat rows of olive trees. In neighboring fields “soft wheat” is cultivated for flour, as well as durum wheat for the semolina used to make couscous, a staple of Tunisian cuisine.

She points to a green plant with delicate flowers. “I’ve also planted leguminous plants like fava beans and others that resist high temperatures and fix nitrogen into the soil. This improves its fertility and ultimately optimizes the growth and yield of my olive trees.”

Her trees are of the Chetoui olive variety which resists the North African heat well but only produces every other year. With her farm certified organic since 2014, Hajabdallah sells the olives she harvests to the local company AGROMED for their organic brand Oriviera which is exported to North America.

“My biggest challenge is irrigation,” she said, gesturing towards the cracked earth. “This is a semi-arid region that’s been experiencing a drought for the past three years. The water table here is low and the water salty. The state doesn’t offer compensation during periods of drought. The past season was okay but last year was bad. The year before that was an excellent year for Tunisian producers.”

“The harvest starts at the beginning of November and finding labor is getting more and more difficult each year,” she said of the challenges faced by local olive farmers. “Using machines is out of the question because they just don’t work for this variety. The olives stick to the branches so we have to pick them by hand. Another problem we have at harvest is that small producers sometimes have to wait a long time to press their olives because the mills get too busy. As you know, olives have to be pressed as soon as possible, within 24 hours, to get a quality oil.”

Further north in another rural landscape near Mateur, 70 km northwest of Tunis located in the governorate of Bizerte, Afet and Selima Ben Hamouda tend to their olive groves. The fertile soil of this agricultural region has been used to grow cereals since the times this was the breadbasket of the Romans.

The Ben Hamouda sisters are in their thirties and part of a new generation of olive growers and producers whose focus is on making extra virgin olive oil of the highest quality. Though they’re the sixth generation to tend their family’s land, they both left their professional careers to do so. In 2015, Afet quit her tourism marketing job while Selima left her career in law to plant an olive grove and eventually launch their own brand, A&S, two years later.

“Our parents were very encouraging and supportive of our decision,” shared Afet. “It was our father who said ‘Why not plant olive trees?’ He pointed out that olive oil is a fast growing industry in Tunisia. People are very surprised and curious when they hear we’re olive producers. At first some of our friends laughed at us, but now a few have planted their own olive trees.”

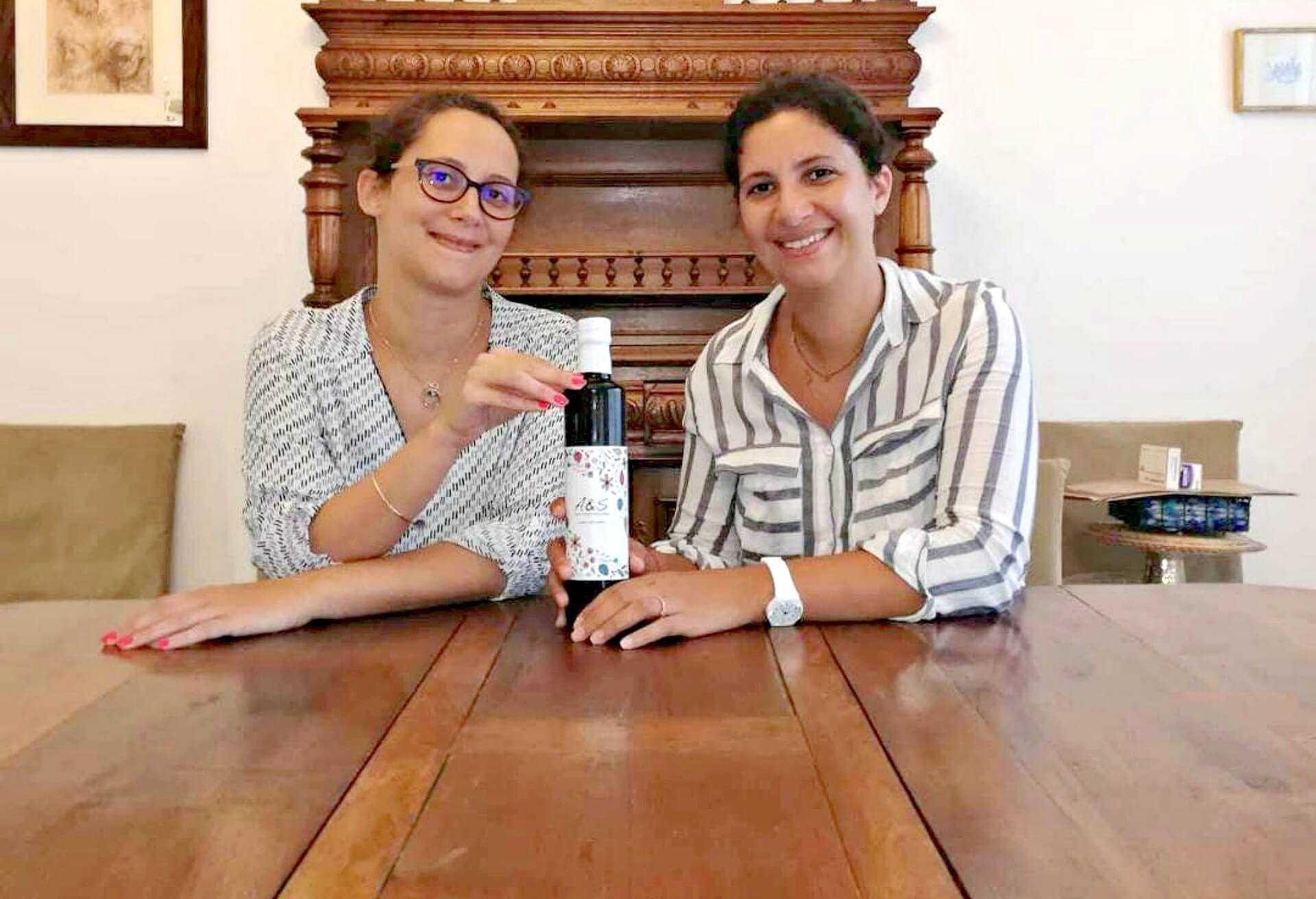

Selima and Afet Ben Hamouda

“We did our research and from the beginning, we knew that we wanted to focus on quality,” Selima added, speaking about their approach to olive production. The sisters traveled south to Sfax to attend a training program by the chamber of commerce covering all aspects of olive production. “About half of the attendees were other women,” she said of the experience. “We got lots of excellent information and advice but also encouragement and support, which continues today.” Wanting to further expand on their knowledge, they traveled to Australia next for further training.

“We continued the work that our father had started on a test plot based on the principles of conservation agriculture,” Afet explained. “The aim is to conserve the richness of the soil so we rotate wheat and legumes every other year, avoid tilling the land, and conserve plant cover to minimize erosion and evaporation. We need to try to keep moisture as much as possible because we don’t get much rain.”

Groves at A&S near Mateur, Tunisia

With 900 Chetoui olive trees already on their land, they decided to plant 12,000 trees of the Spanish varieties Arbosana and Arbquina which produce fruit quickly. Also found in their groves is the Greek Koroneiki variety, a pollinator. “Of course we have to defend our Tunisian varieties too,” Afet ponted out. “So two years ago we planted nine more hectares of our native Chetoui.”

Their obsession with quality extends to all phases of the production process. In order to be able to press their olives as quickly as possible and avoid delays at mills, they invested in their own two-phase milling machine.

Mill at A&S

“This is the only way to ensure quality, by having our own mill,” Selima said of their decision. “The oil mills in this region use a three-phase system which introduces water into the process and the quality is not great as a result. Also, mill operators often don’t separate your olives from those of other producers so everything is pressed and mixed together. So having our own mill was absolutely essential.”

“That first taste of new oil is a very emotional moment,” Afet said, expressing the magic alchemy that happens when months of hard work is synthesized into a green-gold liquid. “We didn’t really plan to have our own label, it just happened. It was the logical next step.”

Awards have come quickly for their brand A&S. Last year, their medium Chetoui extra virgin olive oil won first prize at a national competition organized by the Office National de l’Huile, while their intense fruity was awarded a fourth prize. 2018 has brought more accolades, with awards at well-known international competitions like BIOL Italy, and NYIOOC, where they won a Gold Award.

These two young women who are making a mark on Tunisia’s developing olive oil industry now have an eye on the future. They’re working on building a new building with space for a tasting room and believe that the local industry needs to develop further.

“Olive producers in Tunisia are getting noticed but there’s more to be done,” Afet told us. “We should teach cooks how to use olive oil and there’s also the scope to create specialized olive oil boutiques and develop projects in olive oil tourism. Also, producers need to talk more and communicate. We need to create a group of producers working together on quality production. It’s only together than we can promote the image of Tunisian olive oil.”