At Dievole, Extra Virgin Without Boundaries

The article discusses the Chianti Classico region in Tuscany, known for its wine and olive oil production, and the efforts of entrepreneur Alejandro Bulgheroni to revitalize the olive oil production at the historic estate of Dievole. Despite challenges during the 2014 harvest, they successfully produced award-winning olive oils sourced from olives in Southern Italy, and are focusing on innovation, research, and teamwork to improve quality and accessibility of Italian olive oil. Plans for expansion, experimentation, and sustainability in olive groves and production methods are underway to support this goal.

The countryside between Siena and Florence, in the heart of Tuscany, is one of the most enchanting areas of Italy: a breath-taking, seamless succession of vineyards, verdant woods and huge olive groves interrupted by charming castles and picturesque hamlets.

It’s no surprise it seduced blue bloods, artists and writers over the centuries, luring them to settle down among the gentle slopes and the ancient villages and choose them as the scenery of their works of art.

These days the attraction continues, especially for wealthy tourists and wine lovers. This is the so-called Chianti Classico, a name that defines one of Italy’s most renowned wine DOCGs (Denomination of Origin Controlled and Guaranteed), that owes its origin to an edict issued by the Grand Duke of Tuscany Cosimo III in 1716 to delimit the area.

Moreover, extra virgin olive oil produced by the roughly 400,000 olive trees and 240 growers here can proudly hold the Chianti Classico PDO label. It is however considered somehow a lesser son of this wonderful land and many olive groves lay abandoned or have been replaced by more vines.

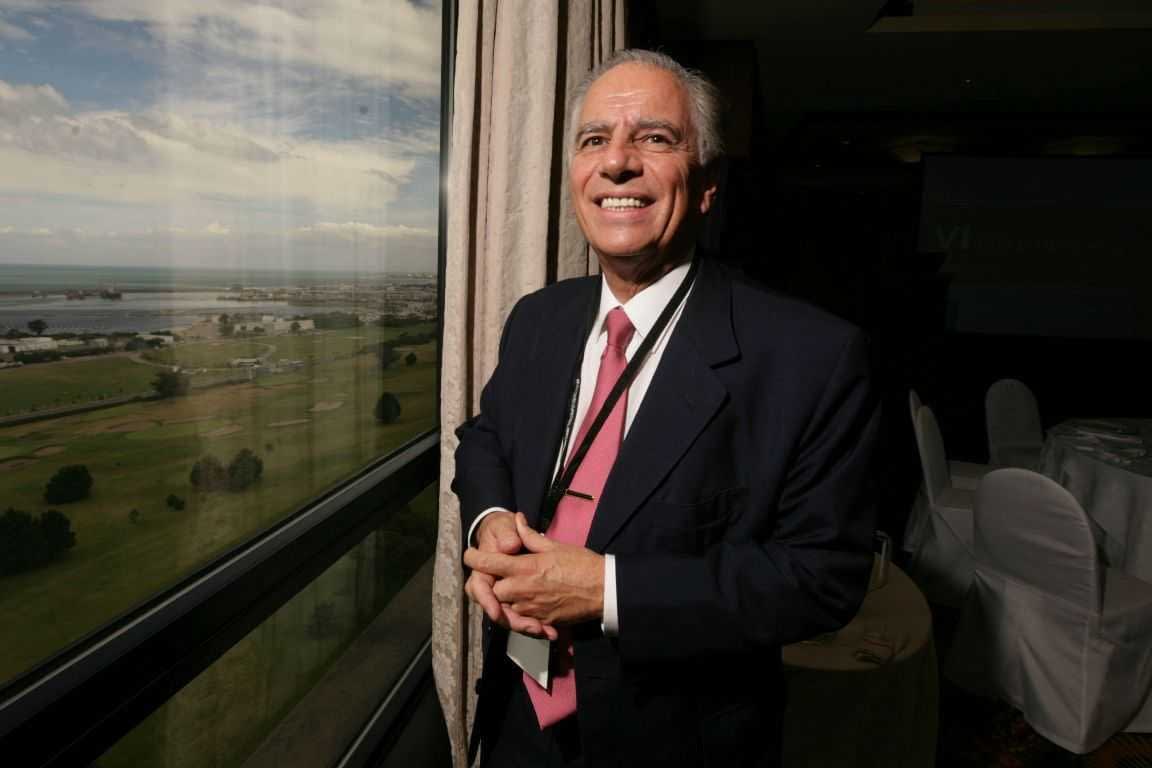

At the end of 2012, Alejandro Bulgheroni — a South American entrepreneur of Italian origin involved in the oil and gas field in Argentina but also an owner of wine estates in Uruguay, Patagonia, Napa Valley and Bordeaux — bought the historic estate of Dievole.

Bulgheroni decided not only to turn back to natural farming and local grape varieties, but to invest in extra virgin olive oil production and olive groves recovery. To do so, he called two people he could rely on: the Tuscan winemaker Alberto Antonini and the Sardinian olive oil producer Marco Scanu. Both had already worked at Bulgheroni’s estate in Uruguay, Bodega Garzón.

Alejandro Bulgheroni

We met Scanu in the lovely Dievole resort, made of luxury cottages, swimming pools and gardens surrounding the old villa at the heart of the estate dating back to 1090. He seemed to have well settled in Chianti Classico as he overlooks an ambitious project which could redefine the traditional Italian oil production: an innovative mill, an olive oil “academy,” a scientific research pool and a lot more to come.

Starting their job at Dievole with the 2014 harvest after one year of planning was not an easy task for Scanu and his staff, which also includes the young production manager Matteo Giusti: Tuscany was particularly affected by the unfortunate year and the project to produce the Chianti Classico PDO and the Toscano PGI extra virgin olive oils could not be achieved.

Scanu found a brilliant solution though, traveling to Southern Italy, where olives were abundant, to buy the best ones before prices rose too much.

The greatest part of the olives processed at Dievole last year came from a huge olive grove in Basilicata, which they personally supervise, and from Apulia: mostly Coratina olives — round and gentler the Basilicata ones, harder and with a stronger flavor the Apulian ones. They were processed together to create a wonderful and well-balanced Coratina single variety extra virgin.

Dievole’s Coratina drew a lot of attention and won a Gold Award at the 2015 New York International Olive Oil Competition. They also brought to Dievole Ogliarola, Leccino and Peranzana olives that, along with Coratina, were used to produce the pleasant blend “100% Italiano,” a gently pungent extra virgin with fresh notes of tomato, green and floral flavors and a balsamic bitter aftertaste.

Olives had to travel for about 600 km, all the way up to Dievole, but this did not worry Scanu.

Marco Scanu

“We were there often to check harvesting and shipment procedures,” he recalls. There was a constant contact between who was in the field and who stayed in Tuscany and the olives traveled and were stored at a steady temperature of 4°C to prevent fermentation. This year, we also monitored the olive groves and we are already starting to organize the harvesting.”

The long transportation weighed on costs, but Dievole insisted on the project to propose quality extra virgin olive oil made in Italy at an accessible price: the 500ml bottles cost around €1 to €15 in Italy, but in tins the price goes down to about €9/liter. “Offering a good quality, 100% Italian extra virgin at an affordable price and in great quantity could be a real thorn in the side of the oil industry selling bad oil, and help more people to get to know what is good olive oil,” Scanu said.

Having been in the olive oil making for 30 years, and having worked for a long time in the huge olive groves in Argentina and Uruguay, Scanu has no preconception against intensive farming or using olives from other regions, or even countries, as long as quality can be achieved. To do so, he points to innovation, research and a strong teamwork.

“We are lucky enough to manage two harvesting and milling processes in one year, between Italy and Uruguay,” he said. “This means local staff can travel and attend each location, and we have the chance to experiment and learn twice in one year.”

To Scanu, research and innovation are key points, and this is why he convinced Bulgheroni to invest in hiring young talents such as Giusti, who were about to finish their job at a local development agency. They experimented on immediate filtration and argon-conditioned bottling, which is steadier than nitrogen and does not affect the oil’s aroma. They adopted a “pre-crushing” for the Coratina olives to smooth their strong character and processed the olives at an average temperature of 18°C.

For the 2015 harvest, the olive mill established in Pianella, not far from Dievole, will be joined by a new, experimental mill designed by Giorgio Mori at TEM, a Tuscan company specialized in innovative machines. And there are further plans of expanding, buying or renting olive groves in Tuscany and in other areas, and setting up an experimental intensive olive grove in Rapolano, near Siena, to plant new varieties and use fertirrigation (uniting a water supply and mineral nutrition to provide a nutrient solution to soil when watering) for meager lands and steep grades.

“We have to make up for lost time, but innovation should not have an end in itself,” Scanu said. “We need to retrieve and uphold Italian competencies, improve quality and let it be accessible to a wider public.”