Waxes in Extra Virgin Olive Oil

It took forever to settle under gravity, and after it solidified following a cold night, it refused to completely ‘melt’ into its natural fluid state after being warmed. My guess was that involved waxes.

Olive oil mill in Messinia

Olive oil mill in MessiniaSome time ago a friend of mine sent me a sample of an extra virgin olive oil, made from the variety Manzanillo and grown in the warm climate of South Eastern Queensland, Australia. The oil was causing her real grief. It took forever to settle under gravity, and after it solidified following a cold night, it refused to completely ‘melt’ into its natural fluid state after being warmed. On face value, there wasn’t anything extraordinary about this oil. Sure, the saturated fat content of the oil was on the high side – not unexpected as hot climate oils generally have lower levels of monounsaturated fat, and nature has to replace it with something! Since saturated fats tend to be solid at fridge temperature, this might explain why the oil partly solidified. But they usually melt again when warmed.

Since then I’ve been called upon to ghostbust a few more of these mysterious EVOO’s. They had a couple of things in common though. They were all Manzanillo’s or dominant Manzanillo blends, and they were all from warm to hot climates. I didn’t have a solution, but I did have a suspect, but until recently the evidence was lacking. My guess was that involved waxes.

The surfaces of a lot of fruits including olives are covered in a thin layer of naturally produced wax. The wax probably acts as a form of bio-armour against attack by plant pathogens like fungi and yeasts, and also provides a valuable barrier against moisture loss. The olive plant is well adapted to semi-arid conditions. It’s not surprising therefore that the surface of the olive has a coating of wax to keep in that valuable moisture when things start to heat up. When olives are processed into oil, the oil that is released dissolves the skin waxes and it ends up in the oil.

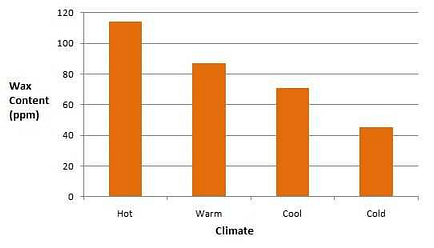

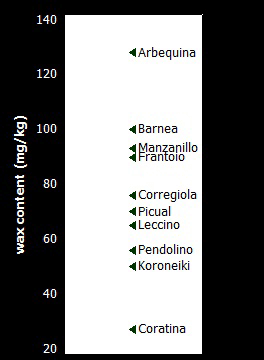

Recently, Rod Mailer and his group (Mailer et al. 2010) published some data on the wax content of different varieties grown in hot (SE Queensland), warm (Central Victoria), cool (SW Western Australia) and cold (Tasmanian) climates of Australia (my categorisation of hot-cold, not theirs).

.

.

Figure 1: Effect of climate on wax content of extra virgin olive oil

.

Figure 2: Average wax content of extra virgin olive oil by variety

.

Ah-hah…. Hot climates produce on average 3x more waxes than cold climates (Figure 1), and of the varieties studied, Manzanillo is number 3 on the list of high wax producers (Figure 2) behind Arbequina and Barnea.

While the amount of wax in an olive oil is pretty small (about 1/8th of a gram per litre), their presence probably act as a seed for other things to solidify.

While the role of waxes in difficult settling and cold solidification hasn’t been proven, it is probably a contributing factor. While there is really nothing a producer can do about it, for some, it is worth knowing why.

.

Reference

Mailer, R.J., Ayton, J. and Graham K. (2010) The Influence of growing region, cultivar and harvest timing on the diversity of Australian olive oil, J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 87:877 – 884.

Richard Gawel’s blog is Slick Extra Virgin. Reproduced with permission.