Archaeological Exhibition Explores History of Olive Oil in the Mediterranean

The exhibition “Wines, oils and perfumes: an archaeological voyage around the ancient Mediterranean” at the Collège de France in Paris showcased archaeological discoveries and objects from various French museums, exploring the production and trade of olive oil and other food products in Roman Gaul, Italy, Greece, and Egypt. Curated by professor Jean-Pierre Brun, the event highlighted the centralization of agricultural goods production during the Roman Empire and emphasized the importance of archaeological research on tools of production and commerce associated with ordinary people to understand the socioeconomic and technological systems of the past.

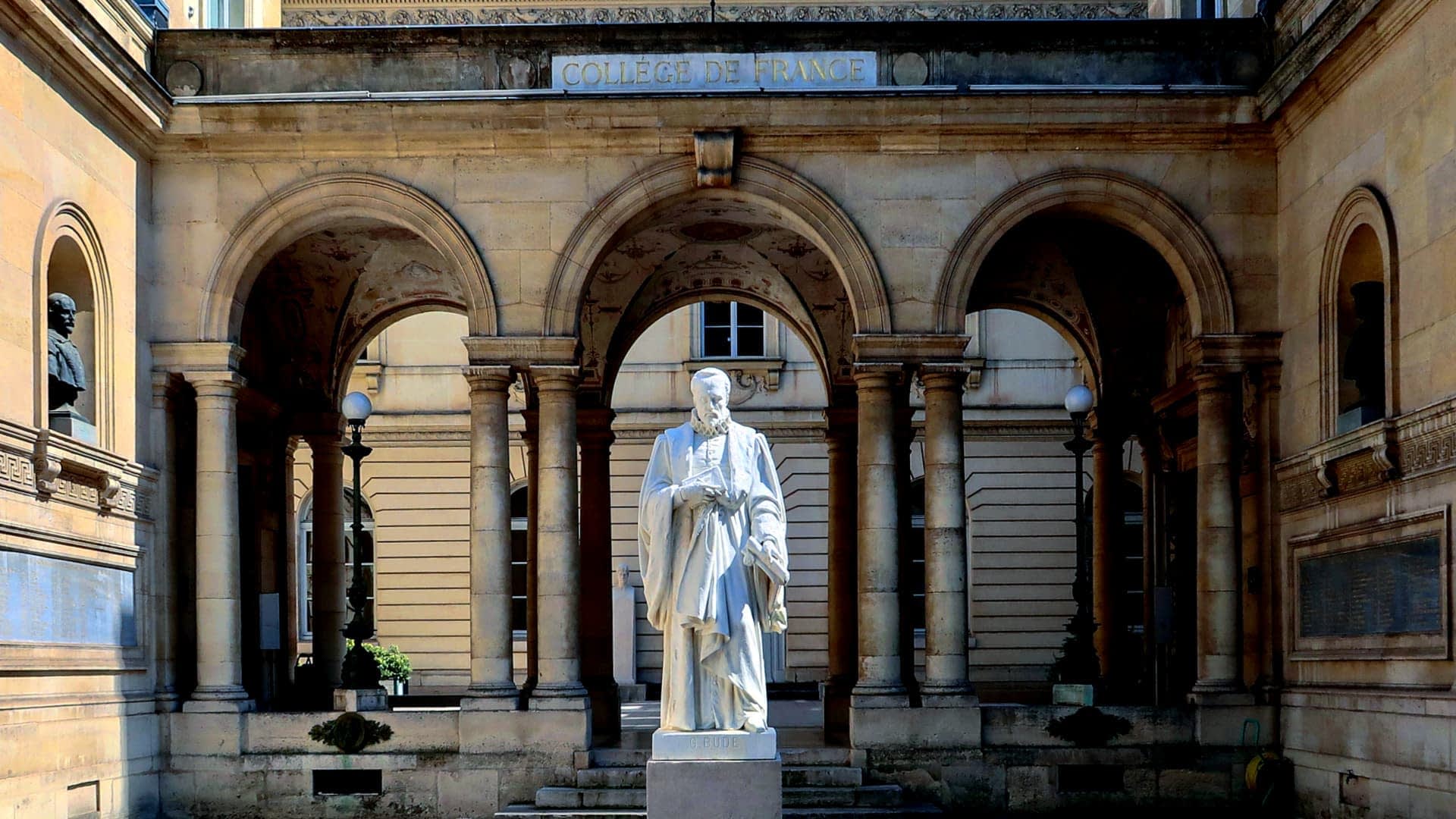

An exhibition at the Collège de France in Paris, a five-century-old public institution of higher education, research and debate, presented archaeological discoveries and objects from several French museums, including the Louvre’s Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman antiquities, from the Archaic period to the fourth century CE.

“Wines, oils and perfumes: an archaeological voyage around the ancient Mediterranean” provided a unique opportunity to explore the production and trade of olive oil and other food products in Roman Gaul, Italy, Greece and Egypt.

Curated by a team of experts led by professor Jean-Pierre Brun—a field archaeologist and senior scientist of the French National Scientific Research Council (CNRS) who has headed the Center Jean-Bérard in Naples, a French base for the historical and archaeological exploration of ancient southern Italy — the event was also a tribute to Brun’s lifelong dedication to archaeology.

See Also:The Olive Tree and The Olympics: An Ancient BondIn his inaugural lecture for the Chair of Technology and Economy in the Ancient Mediterranean, he explained that during the Roman Empire, to achieve an efficient organization and rationalization of supplies to the army and the large urban centers, Sicily and Egypt specialized in grain production and Gaul for wine production, while Spain [the Roman province of Hispania Baetica, corresponding to modern Andalusia] and Africa [mainly Tripolitania, the north African coastal area of modern Libya] specialized in olive oil.

According to Brun, the centralization of agricultural goods production following Roman political power’s demands shaped the conquered territories’ economy and contributed to the structure of the countryside.

This can be seen, for instance, in the remains of ancient olive farms in the Valley of the Baetis, between Córdoba and Seville in Spain — Baetican olive oil production reached its peak between the first and third centuries CE — and in the Tunisian Sahel. These regions were not a priori suited for olive growing.

Nowadays, olive oil is mainly intended for food consumption, and the exhibition recalled its other uses in antiquity.

It was commonly used for medicinal purposes and rituals, as an ingredient in facial creams and as an ointment in personal hygiene treatments and massage at Greek and Roman sporting facilities and thermal baths.

Moreover, in those ancient times, olive oil was also used to fuel oil lamps of different types, some with multiple nozzles. Oil lamps were used for indoor lighting in those areas where production was most prominent.

In perfume-making and other perfumed oils with therapeutic properties, the precious oleum omphacium made from green olives was often used as a carrier oil, particularly in Roman Gaul, Italy and Greece, serving as a natural medium in fragrant formulations.

One of these ancient formulations was on display at the exhibition in Paris, and visitors could also smell the fragrance.

Recreated through years-long research conducted by the Center Jean-Bérard, the antique rhodinon with its delicate rose fragrance was very popular in Greek and Roman antiquity and was also cited in Homer’s Iliad.

The exhibits also included a model layout of the perfumery of the Greek island of Delos, which Challimachus (third century BCE) considered “the most sacred of islands.”

Abundant and complex evidence from archaeological excavations, studying settlements, places and forms of work, food and sanitation has also made Brun ponder questions of growth in antiquity — the fruit of people’s well-being and education.

These findings can be compared with written sources to help better understand the socioeconomic and technological systems of the past.

However, Brun has written about the difficulty of addressing history in all its dimensions when the data available concerning ordinary people is limited.

He has underlined that only partial factual reports and literary commentaries and inscriptions, mainly of the upper classes, are available to historians, considering that “more or less all the written sources from antiquity have disappeared during the Middle Ages.”

These thoughts are relevant today for two reasons. First, there is a risk of losing an archeological legacy through the destruction of material archives, which are those buried in the soil and lost through works and redevelopments.

Secondly, too little attention has been given to archaeological research on tools of production and vehicles of commerce associated with the remains left by ordinary people without the power or the culture to provide written evidence.

The overwhelming scholarly focus on epigraphy (the study of inscriptions on ancient artifacts), sculpture, painting, architecture and urbanism has created a historical bias toward those in power.

Thus, the recent exhibition at the Collège de France can be considered a recognition of Brun’s conscientious and dedicated endeavor to reconstruct a forgotten history of rural and urban masses in their productive roles — including the history of olive oil production and trade in the Mediterranean — and an invitation to reflect on how even Greco-Roman civilization, despite its many successes, has seen decline set in.