Reading the labels of their wine and olive oil bottles, one might think Planeta is an invented brand name referring to the universe of estates and products the Sicilian company has been running and creating over the last 20 years. Instead, this is the real surname of the family whose head of the household currently is Diego Planeta.

After being one of the leading figures of the Sicilian wine’s renaissance working for other wineries, Diego — born to a wealthy, gentry family who always had country estates but never thought about making a living from them — set up his own company in 1995 together with his son Alessio and daughter Francesca, who now lead the company together.

They started with the oldest estate of Ulmo, in Sambuca di Sicilia, and today Planeta Winery counts 6 different estates in every corner of the island, with an overall spread of 363 hectares of vineyards, as well as in Menfi, Vittoria, Noto, Castiglione di Sicilia and Capo Milazzo, and 98 hectares of olive groves in the Capparrina , near Menfi’s beaches.

Planeta’s olive groves in Capparrina, Italy

Planeta’s extra virgin olive oils from Val di Mazara PDO are obtained from traditional and depitted Nocellara del Belice, Cerasuola and Biancolilla olives, and they are as good as the family’s renowned wines.

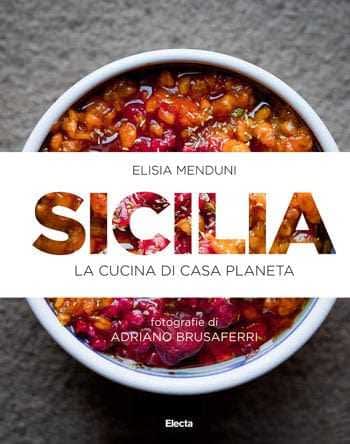

This only partially explains the reason why “SICILIA, the Cooking of the Planeta family” is not an average recipe book. The recently launched volume is not only a cookbook, but, as it is written in the press notes, “a cookery tale about a family and a land, Sicily, which is composed of different territories. It is a travel made of cooking through a land which is the result of several cultural layers, cookery details and knowledge that are naturally accomplished in cooking”.

SICILIA: Planeta Family Cooking

Francesca Planeta herself explains that she strongly wanted this book; it was originally intended as a collection of the cooking classes held at La Foresteria Planeta, a luxury resort where chef Angelo Pumilia runs the restaurant and cooking courses in traditional Sicilian cuisine.

When, however, she asked food writer and food expert Elisia Menduni to help her collect and write the ancient recipes of her family, the project took a different, unexpected direction.

Each member of the family jealously kept them from one another, imagine from strangers. Menduni had to somehow obtain and adapt the recipes from this tight-lipped group and win them over.

Menduni cooked along with Diego Planeta and his sisters Carolina, Annamaria and Marina; thanks to her skillfull cooking, not only she passed the test, but she became a member of the Planeta family.

Family cooking as well as street food were the starting points of the book. In a one-year long job, Menduni and photographer Adriano Brusaferri traveled along the family estates, cooked with them and with chef Pumilia, met the local producers and tasted products.

The huge amount of collected material then became a complete book of 285 pages in dual language Italian and English, and it will continue to feed the dedicated blog (in Italian) where a lot more content will posted, because, as the authors note “written recipes define a culinary code, display a dish in quantities, rules, gestures and techniques. Yet cooking is also made of never-ending revolutions thanks to changes, personalization, versions, adaptations and adjustments.”

The book is a real compendium of the traditional Sicilian cuisine, including land and seafood, peasant and noble food such as the famous timbales.

The house’s wines and oils, too, have a prominent role in the book, as each recipe comes with the ideal matches to one or more Planeta’s products. While wine pairings are selected by journalist and wine taster Filippo Bartolotta, olive oil were chosen by Menduni:

“I was lucky enough to have the three different Planeta extra virgin olive oils, the two depitted monovarietal oils from Biancolilla and Nocellara del Belice olives, and the Traditional blend also featuring Cerasuola. Each of them has its own distinctive character and they can cover the whole Sicilian gustative world. Biancolilla has delicacy as its main feature and it’s ideal with raw, delicate food. Nocellara gives a more intense oil to go with rich flavors, while the robust Traditional Blend is a perfect expression of the “Sicilian soul” with its beautiful notes of tomato skin and artichokes, and I chose it for the most traditional dishes.”

Among the recipes where extra virgin plays a key-role were the canazzo — a kind of “ratatouille” made of raw and cooked vegetables where extra virgin maintains the harmony between the different flavors; and the olive oil potato mash, a favorite at the Foresteria, where the potatoes are only mixed with water and extra virgin olive oil.

The food writer underlines that extra virgin olive oil was used for all the fried recipes with the only exception of the famous arancine (rice balls), and she reveals one of the secrets of the Planeta’s cookery: they often add one or two spoons of the oil used for frying the food to the final recipe. “This may seem odd.” Menduni said, “but I have to say it really works, because the frying oil gives the dish a gluttonous cooked note that adds roundness to the final taste instead of the usual freshness of raw oil, such as in the spaghetti with fried courgettes and fresh mint leaves.” (Recommended only when you use a very good extra virgin and pay attention to frying temperatures.)

The company’s harvest was a luckier one compared to other Italian producers this season, thanks to the ideal location of the olive grove where olive flies arrived but didn’t bred. “After a standard winter, we had very few rain showers in late spring until the harvesting time,” Alessio Planeta noted, “and this caused the soil to be quite dry. A cool summer favored the diffusion of insects responsible for the fruits’ drop. We had few olives, but of average quality for a harvest that will be remembered as one of the scantiest, ever. Oil output, however, was higher than last year’s.”