Revolution, Hope and Tunisian Olive Oil

Raouf Ellouze and Karim Fitouri were drawn back to Tunisia at times of political upheaval and change. Now, they want to help Tunisia become known for world-class olive oil.

Raouf Ellouze and Karim Fitouri are two men in Tunisia with different backgrounds who have come together to help Tunisia become a world-class olive oil nation during times of political change. Ellouze is a gentleman farmer who has been working on expanding his family’s estate and creating a unique blend of olive oil, while Fitouri, a former London businessman, has devoted himself to understanding olive oil and is determined to change Tunisia’s image through his Olivko brand.

This is the story of two very different men drawn back to Tunisia at times of political upheaval and change, and how their desire to make great olive oil now unifies them in an effort to help Tunisia become a world-class olive oil nation. An Olive Oil Times reporter spent time with both men to learn their stories.

We have big horizons. We have a unique quality. We don’t use pesticides and for this, the quality is unique.

Raouf Ellouze: A Gentleman Farmer Remakes the Tunisian Olive Plantation

Raouf Ellouze can be driving along and on the spur of the moment be induced into song.

At one point, driving through his home city of Sfax at the end of January, he breaks into Chuck Berry’s “Johnnie B Good” and cracks a big warm smile.

Then his cellular phone rings, and he’s carried off into one of his many business calls.

Ellouze, 64, is a scion of one of Sfax’s landed gentry families – one of the “grand familles,” as he called them – and as a consequence also inherits a large country estate – an estate that spreads out for 21 square kilometers (8 square miles).

At the turn of the 20th century, it was common for wealthy families from Sfax to start estates in the arid pasture land surrounding the city and plant huge plantations of Chemlali olive trees, which make a sweet and light olive oil.

That’s what his family did in 1910: They hired farmhands and, taking water from shallow wells dug in the sandy ground, and began planting. The trees were kept alive thanks to well water brought by camels and workers carrying jugs.

He’s a reflection of his upbringing. Ellouze is learned (as easy singing 1960s songs as talking about world history), enjoys refined tastes and comes across as a blend of cosmopolitan modernity and traditional Tunisian values and thought.

According to family lore, his ancestors came from Andalusia in the 15th century, selling almonds. Over the centuries they continued trading, he said.

He is now in the middle of turning his very own personal blend of insights into his Domaine Chograne extra-virgin olive oil.

Ellouze is 16 years into a project to expand his family’s estate, principally by planting thousands of new trees to create his own blend of polyphenol-rich extra-virgin olive oil made from new Chemlali, Chetoui and Koroneiki trees.

“I was fed up with the sweet taste” of Chemlali olive oil, he says, speaking English with a French accent. “I knew I couldn’t keep on with the bland taste (of Chemlali) to sell in Italy. So, that’s why I went for this project.”

Instead of Chemlali, which he says loses its pungency after a couple of months, he is looking for a strong, aggressive taste — one that Tunisia’s robust northern olive, the Chetoui, is famous for. He now sells his bottles in France and the United States.

Becoming an impassioned olive oil aficionado, though, wasn’t always in the cards.

He studied veterinary sciences at university in Tunis and then found work as a breeder in the royal stables of Saudi Arabia. “I had a fabulous time there,” he said. “It was on the Red Sea. I went diving, snorkeling, fishing.”

But then in 1987 something big happened back in Tunisia. A coup d’etat brought down the government of Habib Bourguiba, Tunisia’s first Arabic president after independence from France, and Ellouze said he returned to his homeland hoping that General Zine El Abidine Ben Ali would bring democracy.

“I wanted to come back to Tunisia. I hoped for democracy. Everybody believed in that,” he says, negotiating Sfax’s incessantly abrasive traffic.

As it turned out, democracy was not in the winds. Ben Ali remained in power until Tunisia’s 2011 revolution — the beginning of what has become known as the Arab Spring.

Nonetheless, Ellouze remained in Tunisia and began a new chapter in his life: Tending to his family’s estate far out in the olive groves of the “Thirsty Valley,” as the extensive plains surrounding Sfax are called due to the lack of rain here.

Today Ellouze is part of a new generation of olive oil makers in Tunisia. “There is no future for the old plantations,” he says.

The old plantations of Sfax, planted as they were with Chemlali trees, need to follow his example and evolve, Ellouze says. He’s looking for more complexity in his oil. He believes more plantations need to follow his example for Tunisia to become successful on the international market.

He says Tunisians should continue cultivating their unique varieties, but also experiment with native cultivars and expand the range of taste in their oils.

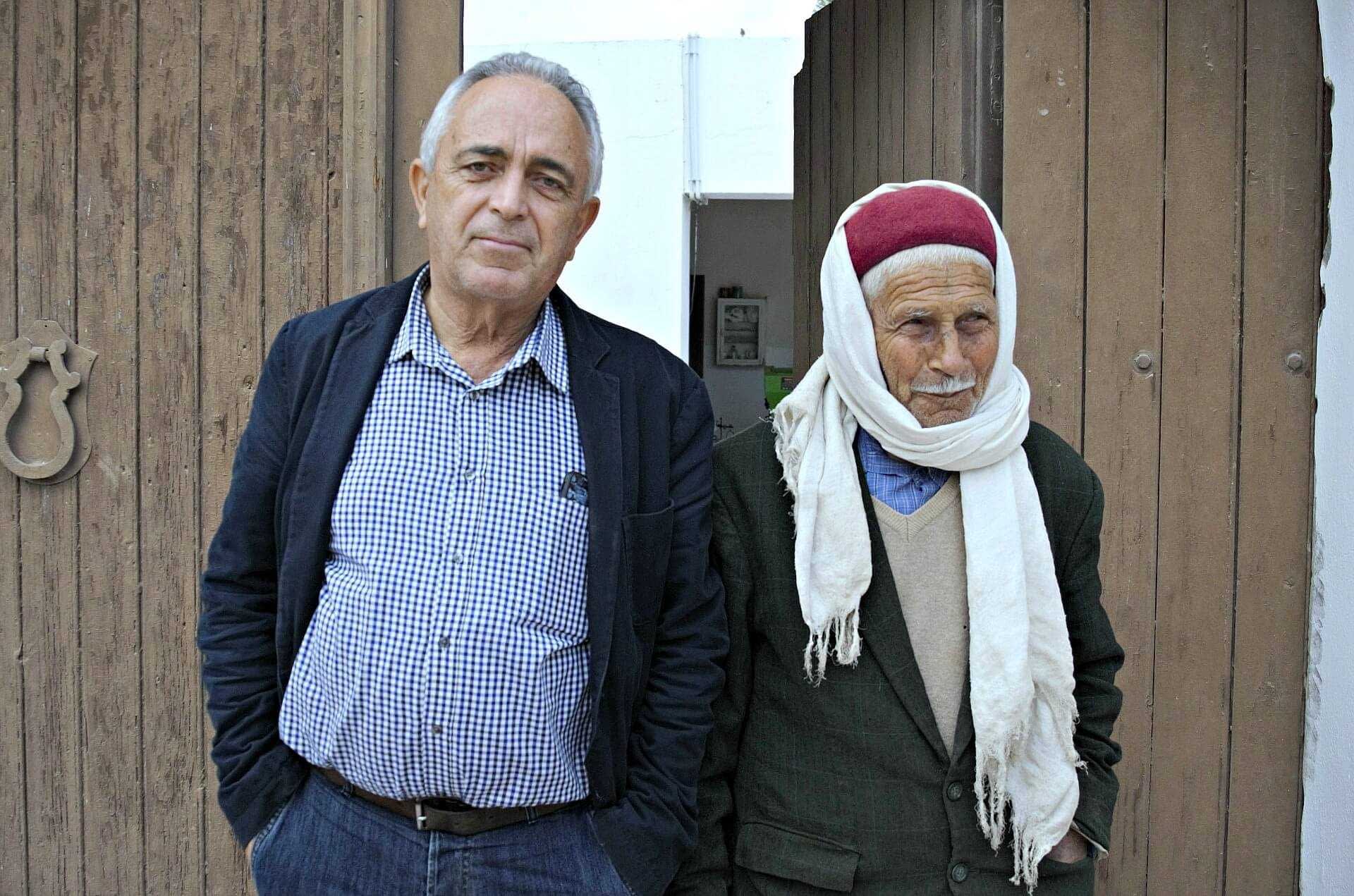

Not everyone agrees, of course, among them his own father, who is 91. “My father thinks I am crazy,” he adds with a smile.

Raouf Ellouze inspects olives at a mill in Sfax

His own evolution took some time, too. In 2000 he went traveling to discover how oil was made in other places, and his journeys helped him form new ideas on how to make high-quality olive oil in Tunisia.

During that period, he traveled to Greece, France and Italy, tasted a variety of oils and talked to a range of producers. In Greece, he found tastes that he particularly liked.

When he returned to Tunisia, he decided to plant thousands of trees of the Greek varietal Koroneiki.

He also wanted to follow the example of an Italian producer he met: That producer had a mill in Tuscany that made only 4,000 liters of oil, but it was of excellent quality and sold for a high price.

“I understood we could do like Italy — high-quality oil at a high price,” he said. Over time, he grew more convinced about what he wanted to do. “I wanted to create an oil that I like to taste,” he says.

As a national leader among Tunisia’s olive farmers, he is on his phone often, engaging in promoting Tunisian olive oils on the world stage.

And he is sanguine about the future of his country.

“We have in front of us a huge …” he pauses and searches for what he wants to say. He finds it: “New consumers.”

“We have big horizons. We have a unique quality,” he adds. “We don’t use pesticides and for this, the quality is unique.”

Ellouze is full of energy – and ideas. He wants to improve olive oil not just in Tunisia but everywhere. He is a believer in the potential for olive oil to become one of the world’s most unifying elements.

As he drives toward his domaine, he points out the olive groves growing in arid and sandy, dead-looking, soils.

“Look at the sand. It is the best,” he says, causing this Olive Oil Times reporter to marvel at his statement and the arid landscape.

“Why?” This reporter asks, incredulous.

“Sandy.”

“Why?” The reporter ponders out loud, thinking about why sandy soils might be an advantage to a tree’s growth. The only obvious reason could be that sandy soil might allow roots to extend with ease and thus find water.

“Because the roots can go down?”

“Yes, the roots can go down.”

The conversation turns then to the issue of water.

Ellouze says water can be found even 10 meters under the surface, and that much more is found is found between 20 and 40 meters underground.

But what’s more interesting is this: 80 meters below where he is driving there’s very good water with very low salinity, he says.

“That’s the miracle,” he proclaims as he drives farther into a vast arid and sandy plain full of healthy olive trees, the heart of Tunisia’s olive oil production.

Back in Sfax, a chaotic city with one of the Arab world’s most complete medinas, the traffic is hectic.

Ellouze is again on the phone, incensed over negative comments made about Tunisian olive oil at the recent olive oil festival he helped organize in Sfax at the end of January.

With firmness and a gentleman’s candor, he puts down the phone and curses. He drives on, and out of nowhere defended his city.

“A lot of people say Sfax is dirty, with lots of traffic. But I love my city.” We drive into a city pulsating with life.

Karim Fitouri: Creating Olive Oil Made for Tunisia, and Talking Revolution

Karim Fitouri, a 45-year-old olive oil producer some are calling Tunisia’s olive oil ambassador, is driving through southern Tunisia in a place not far from the Sahara Desert and he’s strangely ebullient.

Karim Fitouri

In this arid, dry and seemingly hostile landscape of nude hills, sandy vales and scrubby plains he sees potential: He says the future of Tunisia’s olive oil industry could be written here.

“There is water,” he says with characteristic enthusiasm and determination in a soft English accent he picked up from living in London for much of his life. “There is good water under the desert … I think the future of the tree is in the desert.”

He is not mistaken. Scientific studies have mapped large reservoirs of water here.

Fitouri’s appearance in the desert, on the lookout for olive trees along with an Olive Oil Times reporter, and his sudden rise to become one of Tunisia’s most promising olive oil makers actually have origins in a stylish lounge of a Four Seasons hotel half-way around the planet.

It was 2012. Tunisia’s long-time dictatorship had been overthrown a year before and Fitouri, who’d built a very successful business in high-end chauffeuring in London, wanted to take part in this new Tunisia.

“I wasn’t satisfied,” he says about his life in London. “The revolution happened in Tunisia.”

The changes and the opening of the country, he says, was sparking a construction boom. “When you build, you have to furnish it,” he says with the matter-of-fact manner of a businessman.

So, he came up with the idea of going to China and importing Chinese furniture into Tunisia, but while he was there his business sense told him that instead of buying from China, “I wanted to sell to them,” he recalls.

He racked his brain. “What do we have in Tunisia? Olive oil, dates, salt, phosphate,” he says, recalling his mental gymnastics. “So, I said, ‘OK, olive oil.’ I knew nothing. Zero. I didn’t even know there were varieties (of olives). This was four years ago.”

He managed to arrange a meeting with two executives of a Chinese supermarket chain to persuade them to buy olive oil. For the meeting, he got some oil from a friend who owned a mill and he bought some bottles at a duty-free shop in Tunisia.

Armed with five bottles, he met the executives – a man and a woman – at the Four Seasons hotel in Guangzhou, China.

“The bottles looked good,” he says. “They started sniffing it. They liked it. They said, ‘This is good oil. Where is it from?’ ”

“I said, ‘Tunisia,’ with pride. Then he said: ‘Oooh.’ I don’t buy from Tunisia.”

“Why?” Fitouri asked the man.

“Because I bought once from Tunisia. The second time they conned me and sent me a bad oil. Now I buy from Australia.” And that was that.

But not for Fitouri. On the airplane ride back home, he was dumbfounded and more than anything offended and hurt.

“What the hell was that?” he remembers thinking. “I know Tunisia has good oil. I was offended and that made me want to find out what the problem was here in Tunisia” with its olive oil.

Fast forward to today. Fitouri’s brand, Olivko, won a prestigious Gold Award at last year’s New York International Olive Oil Competition, and his star has risen quickly in Tunisia.

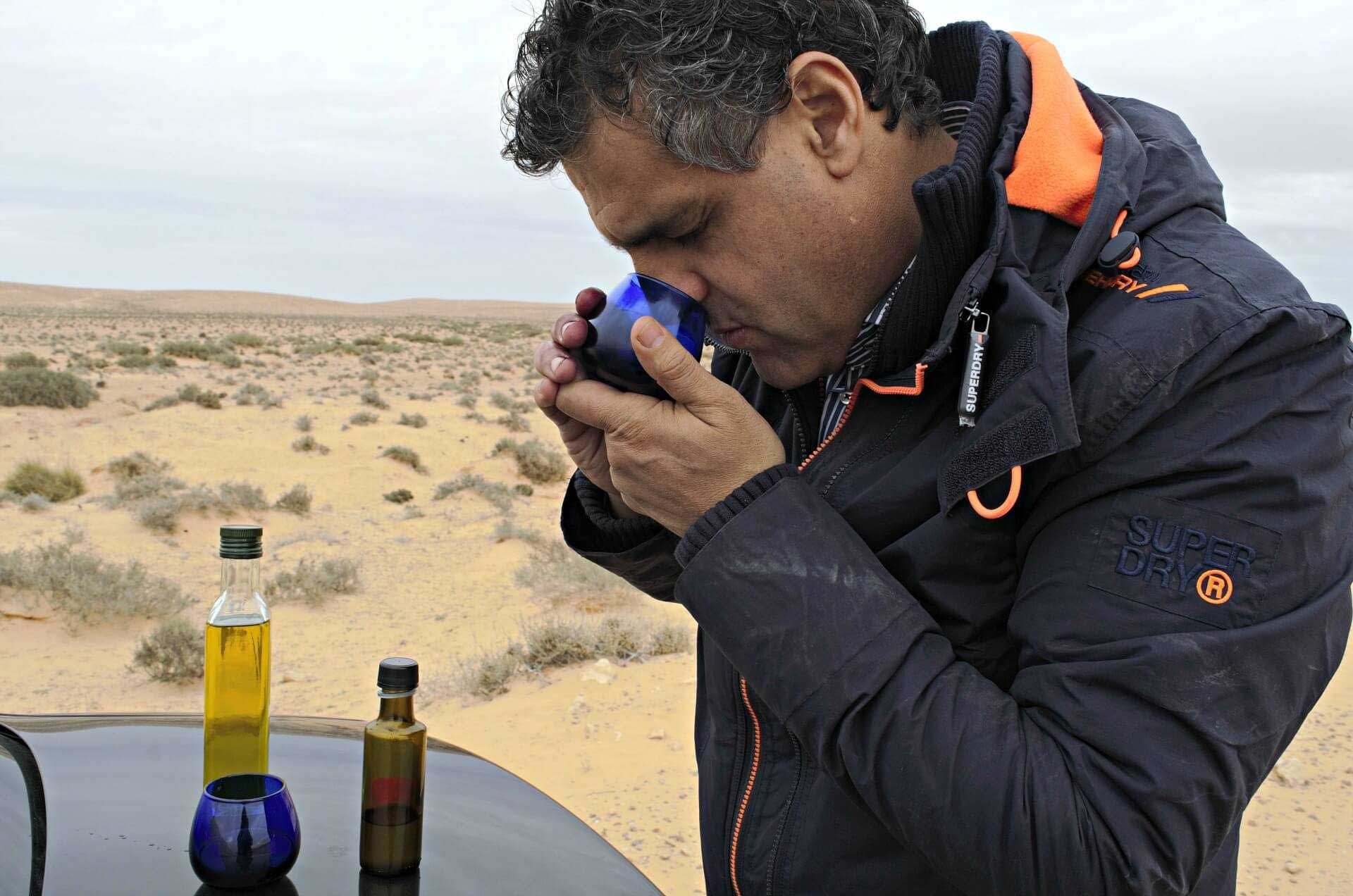

Following his disastrous venture in China, Fitouri devoted himself to understanding olive oil. He carries a set of olive oil sommelier’s glasses with him when he goes traveling.

Since returning from China, Fitouri has traveled throughout Tunisia, tasting olives, meeting farmers, hand-picking varieties and crops for his Olivko brand — all in an effort to blend Tunisian varieties into excellent oils.

The road is long and straight. The semi-desert landscape extends in all directions. Every once in a while patches of olive trees are seen.

Then he spies the profile of a massive tree in the distance. “I want to see it, it looks big,” he says.

He gets out of his car and clambers over an embankment and scrub, all the time admiring the big foliage-rich tree that is made up of a forest of trunks. He is in awe. There are olives on it. He crushes them in his fingers and smells the pulp. It’s a pleasing fragrance.

“This is an old tree, this,” he says. “This one must have thousands of years.” He climbs into its branches.

“It has a lot of water,” he says, back on the ground. “So it is deep. Fifty meters down.”

He puzzles some more over the olives in his hand. “This is a different variety,” he says. “I have not seen this variety before.”

“This is the thing I want. Come down here. See it (when the olives are green). Press the olives,” he says. “This would give you a good oil.”

He pushes on, wonders out loud about bringing a mobile olive oil mill down here into the desert to make oil from these trees in the middle of nowhere.

“Look at this,” he says, driving past scrubby arid plains. “This is all a waste. You could plant 10 million trees here.”

The conversation turns to whether Chemlali olives can be turned into a quality olive oil. On the spur of the moment, he pulls over and goes to the trunk of the car and brings out a box with olive oil bottles and blue tulip-shaped sommelier glasses.

On the side of a desert road, he commences a tasting, his mouth noisy doing a strippaggio to taste a Chemlali oil he made.

It certainly is good.

“When you process it correctly, ship it correctly, you can have a good Chemlali,” he says.

And he drives on, talking about how Tunisia can become the world’s best land for olive oil.

“This is all organic. Untouched.” The desert goes on, and Fitouri doesn’t stop talking.

“I am creating history here in Tunisia. I am doing a revolution here in Tunisia,” he says. “Changing the image of Tunisia as a whole. Everyone will know olive oil from Tunisia.”

He sees himself not only making olive oil but also helping Tunisia realize its revolutionary goals of transforming into an open and modern nation.

“Half the world thinks Tunisia is not safe. It hurts me. It is safe. We can stop anywhere and talk to the people. I feel very safe,” he says.

Then it’s on to his new business pursuits: Putting his oil into tuna cans (“Why should you have a lampante oil with tuna?”) and building an estate for Olivko in northern Tunisia where people can learn how to make olive oil and adopt trees they can personally prune and pick.

Maybe it was always his destiny to be an olive oil man.

Indeed, he says in Arabic the word fitoura means “olive paste” and kids jokingly called him that when he was growing up on the island of Djerba, the son of a hotel manager.

“You know,” he says, “I love the bloody tree.”

Share this article