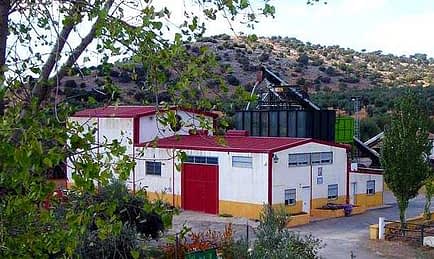

One of the high points of a recent, very rainy trip to Andalusia was a visit to Almazara Caseria de la Virgen, an organic olive farm and mill near Alomartes, about an hour west of Granada. The gracious hospitality of owner Antonio J. Lopez Rodriguez gave me my first view of a fully organic tree-to-market olive oil operation. A guided tour of the trees, the machines and the bottling operation provided an insight into just what is involved in producing organic olive oil.

Bottled under the ‘Ecolomar’ label, Caseria de la Virgen oil comes from 9,800 trees of four varieties: Lucio (a relatively rare variety native to the immediate vicinity) Picual, Hojiblanca and Picudo. The organic Lucio oil I took home is also, unsurprisingly, the one extracted from olives chosen to be cultivated on Granada’s 52-acre, 5,000-tree grove of Alhambra Generalife nearby.

Sparing the reader the standardized organoleptic terminology (which I do not have the expertise to employ anyway), this unfiltered oil was wonderful. Extra-virgin blends from the four varieties produced on the farm are also available and subject to the same strict standards required to be certified organic (by Andalusia and by the EU) and protected by the Designation of Origin of West of Granada.

But this is much more than an olive farm; it is a farm school where children learn about olives, the extraction process and marketing of olive oil. After going through the hands-on process with equipment scaled down to their size, students produce olive oil which is then bottled with a label of their own designs.

In a time when young people, especially around the Mediterranean, are faced with employment and environmental crises, and financial constraints on the ability to consume quality foods, such an institution takes on an added importance in preserving cultural and environmental quality and a treasured way of life. It should be a model for olive oil operations around the world.

When I asked Mr. Lopez Rodriguez why he switched to organic some twelve years ago, after three generations of producing fine olive oil, he told me that if you do something you love, you always want to do it better, and “unless you actually prefer pesticides and herbicides,” organic is unquestionably better. In a country threatened by erosion, pesticide and herbicide pollution and fertilizer runoff, it is an obvious choice.

When I asked him about the problem of olive flies, he said it is not as big a problem as pesticide sellers would have us believe and can be dealt with by traps and other local methods. Believe it or not, one common and effective way of dealing with flies around the Mediterranean is by hanging plastic bags filled with water. The flies are repelled (who knows why – it doesn’t matter) by the reflection of light on the water. I’ve seen it myself. Like the choice to go organic, sometimes it’s as simple as that.